Isodense Acute Epidural Hematoma

G. Michael Lemole, Jr., MD

Jeffrey S. Henn, MD

Joseph M. Zabramski, MD

Division of Neurological Surgery, Barrow Neurological Institute, St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center, Phoenix, Arizona

To diagnose acute epidural hematomas, physicians must consider a patient’s clinical status and be aware that epidural hematomas can appear as isodense collections. A 37-year-old male was an unhelmeted driver involved in a motorcycle accident. He lost consciousness and was combative upon his arrival at the trauma center. By report, the patient was moving all extremities and screaming. He had suffered external head injuries, including a right frontal scalp laceration. He demonstrated a right racoon’s sign but no Battle’s sign. No skull fractures were palpable.

At the time of neurosurgical assessment, the patient had already been intubated and paralyzed pharmacologically. His right pupillary reflex was sluggish and the left pupil reacted briskly. The diameter of both pupils was 5 mm. Upon admission, his hemoglobin and hematocrit values were 10.9 g/dl and 33.2%, respectively.

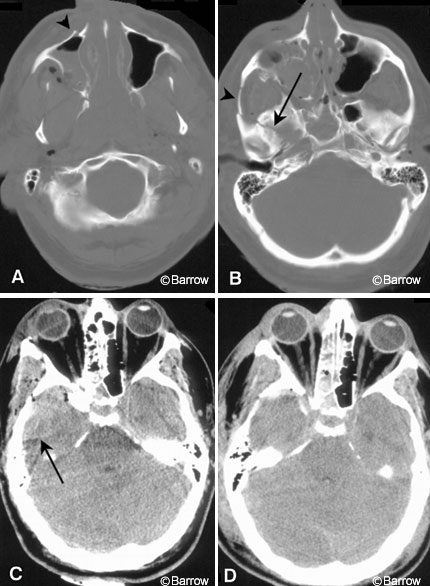

Computed tomography (CT) of the head obtained on an emergent basis showed numerous fractures in the patient’s skull and facial bones. A tripod fracture on the right included the lateral wall of the maxillary sinus (Panel A, arrowhead) and zygoma (Panel B, arrowhead). Fractures extended along the floor of the frontal and temporal fossae (Panel B, arrow). An isodense mass lesion (Panel C, arrow), 3×4 cm, occupied the anterior right temporal fossa. A thin hyperdense line separated this collection from the adjacent brain. No significant midline shift was associated with this lesion.

The diagnosis was unclear at the time the CT scan was obtained, but the patient’s neurological status and the fractures through the temporal fossa floor suggested the need for surgery. A right pterional craniotomy was performed, and a subtemporal epidural hematoma (100 ml) under considerable pressure was evacuated. The source of the hemorrhage was considered to be one of the many fracture lines through the temporal fossa floor. Upon recovery from anesthesia, the patient was neurologically intact and moved all extremities upon command. His pupillary responses were brisk and symmetric. Follow-up head CT (Panel D) confirmed complete evacuation of the hematoma with no associated parenchymal brain changes.

The CT appearance of an acute epidural hematoma of clinical significance is usually unambiguous: a convex or lentiform hyperdensity. Isodense acute epidural hematomas are rare. A low hematocrit (9-11 g/dl) in a patient with an epidural hematoma may influence the radiographic appearance of the clot. The subtle findings on this patient’s CT had to be weighed against his clinical examination in the presence of extensive skull fractures. Given the size of the hematoma, it is surprising that the patient was not more symptomatic. Perhaps, however, the location of the epidural hematoma in the anterior subtemporal fossa permitted upward displacement of the temporal lobe rather than medial displacement and uncal herniation. Nonetheless, these lesions are potentially fatal and must be addressed emergently if their size and location warrant intervention.