Review of Arachnoiditis Ossificans with a Case Report

Archana C. Lucchesi, MD*

William L. White, MD

Joseph E. Heiserman, MD†

Richard A. Flom, MD†

Division of Neurological Surgery, †Division of Neuroradiology, Barrow Neurological Institute, St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center, Phoenix, Arizona

*Current Address, East Valley Diagnostic Imaging, Mesa, Arizona

Abstract

Arachnoiditis ossificans is a rare type of arachnoiditis, with about 46 cases reported in the world literature today. It has received little attention in the neurosurgical literature. Spinal arachnoiditis ossificans can present with a wide variety of signs and symptoms, depending on the location, morphology, and size of the lesion. Predisposing factors for the development of the disease are similar to those for adhesive arachnoiditis and include trauma, hemorrhage, and meningeal irritation. Unlike adhesive arachnoiditis, arachnoiditis ossificans has been treated successfully with surgery. Surgery, however, remains a controversial treatment option. Consequently, the literature and available case reports on arachnoiditis ossificans were reviewed to gain a better understanding of the disease, its presentation, etiology, treatment options, and prognosis. The disease is optimally evaluated by noncontrast computed tomography. Treatment decisions are based on the location and morphology of the calcifications and their contribution to compression of the spinal cord or nerve roots. Most patients with arachnoiditis ossificans do undergo surgery and most improve.

Key Words : arachnoiditis, back pain, CT myelography, magnetic resonance imaging, ossificans

Spinal arachnoiditis ossificans is a rare entity, and its true incidence is unknown.1 Virchow first differentiated between symptomatic and asymptomatic calcifications, and Puusepp25 is credited with describing and treating the first four cases of the disease in 1931. In 1971 Kaufman and Dunsmore9 proposed the term arachnoiditis ossificans for the more ominous manifestation of the disease with clinical symptoms. Incidentalarachnoid calcifications, which are found in as many as 76% of spines at autopsy, differ from the symptomatic, progressive form of arachnoiditis ossificans, which can lead to devastating neurological sequel-ae.9 These distinct clinicopathological entities differ in terms of their etiology, clinical course, and prognosis.9Arachnoiditis ossificans, which forms the basis of this article, applies to the latter manifestation. The case reports on arachnoiditis ossificans in the literature were individually reviewed and analyzed in an attempt to clarify the role of surgery in the treatment of these patients. An additional case is also presented.

Methods

A computerized search of the medical database Medline (1966 to current), performed using the key words arachnoiditis, ossificans, and calcifications, provided 16 articles (21 case reports).1,4,6,8,12,17,18,27-29,32-34,36,39,40 The reference lists that followed these articles provided 11 additional articles (17 case reports) dating to the early 1900s.2,5,9,10,13-15,20,21,25,37 A Japanese article32 included a table in English that provided information on four additional case reports from the Japanese literature. Foreign articles that could be translated were included in the study.2,15,27 Articles were obtained from the medical library at St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center or by interlibrary loan.

The following exclusion criteria were established after these articles were reviewed: (1) asymptomatic patients or autopsy reports,7,11,24,30,31 (2) information unavailable in English or not readily translated,3,16,41 (3) pertinent information not reported,26,38 and (4) compression due to an osseous anomaly.22 Our patient (presented below) was also included in the analysis.

Patients were evaluated in terms of age, sex, location of the calcifications, and treatment. Patients treated surgically were further evaluated for level of surgery and surgical outcome. One patient with disease at T10-L2 was characterized as having lumbar disease because the nerve roots of the cauda equina were involved.40 Another patient had two isolated sites of disease, which were considered separately as thoracic and lumbar arachnoiditis ossificans.10 Patients were diagnosed either by computed tomographic (CT) examination or at surgery, some of whom also had a diagnosis based on pathological analysis.

Illustrative Case

In October 1996, a 64-year-old female with a 2-year history of back pain sought treatment at our institution. She subsequently developed right back pain and numbness in the right lower extremity. She also experienced mild urinary retention. In 1950 she had undergone a lumbar discectomy with spinal fusion at L4-5 and L5-S1.

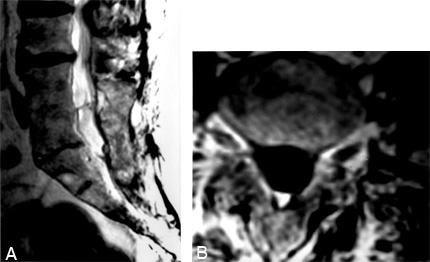

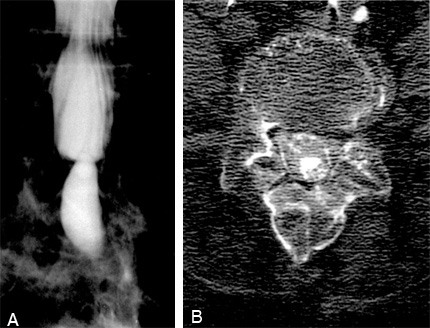

Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging showed changes associated with arachnoiditis (Fig. 1). There was no mass and no evidence of herniated nucleus pulposus or stenosis of the spinal canal. Lumbar myelography with CT confirmed the findings (Fig. 2). However, the calcific nature of the disease was not apparent until a follow-up noncontrast CT was performed 9 days after the myelography (Fig. 3). The calcifications, which were very fine and scattered throughout the dural sac from L4 through S1, involved the nerve roots of the cauda equina. Because calcifications were present, surgery was considered a viable treatment option.

Because the densities were so small, however, and because she also had concomitant medical conditions, surgery did not seem indicated. The patient was placed on ongoing pain medication, and physical therapy was recommended to improve her ability to ambulate. She continues to have pain and urinary dysfunction, which are attributed to the arachnoiditis ossificans.

Results

Forty-three patients with arachnoiditis ossificans were identified in the literature, including our case report described above.1,2,4-6,8-10,12-15,17,18,20,21,23,25,27-29,32-37,39,40 Altogether, there were 19 males (44%) and 24 females (56%). Their ages ranged from 21 to 77 years.

Among the 43 patients, calcifications occurred at 44 locations or sites. There were 23 (52%) thoracic cases and 21 (48%) lumbar cases.

Of the 44 sites of calcification, surgery was performed on 37 sites (the patient who had both thoracic and lumbar disease had two separate surgeries and thus was placed in both thoracic and lumbar categories; Table 1). Six patients did not undergo surgery, and the treatment of one patient could not be determined. Of the 37 surgical cases, 21 patients had thoracic and 16 had lumbar disease.

Of the 21 patients who underwent thoracic surgery, 12 improved, 6 were unchanged, and 2 worsened. The surgical outcome of one patient could not be determined. Of the 16 patients who underwent lumbar surgery, 10 improved, 4 were unchanged, and 1 worsened. Again, the surgical outcome of one patient could not be determined. Six patients (including ours) did not have surgery for the following reasons: One patient had preexisting T5 paraplegia;1 two patients had mild or stable symptoms:8,20 and three showed very fine calcifications adherent to nerve roots8 (Table 2).

Discussion

Arachnoid calcification and ossification first became of interest in the late 1800s. Many of the early cases, however, occurred in the brain, and dural and pia-arachnoidal calcifications were not differentiated from each other.30 Although dural calcification is more common in the brain, arachnoidal ossification is more common in the spine.30 In the 1930s Virchow observed that these calcifications could be asymptomatic and attributed them to the degeneration of connective tissue into osseous tissue.25

By 1957, 17 cases of arachnoiditis ossifications had been reported.30 The increase partly reflected improved surgical technique, which permitted more laminectomies to be performed and hence increased the likelihood of detecting the disease.30 A resurgence of articles appeared in the 1980s when the workup of back pain was aided by the advent of CT, which provided excellent visualization of the calcifications. The exact number of cases reported in the literature, however, is unclear. By 1990, one author cited 41 cases,10 and in 1995 another author cited 55 case reports.34 We were able to identify only 46 cases (43 of which were included in the review; three cases were excluded because we could not translate them). Thus, the differences in the number of reported cases may reflect exclusion criteria and language barriers.

Other discrepancies between the current review and the literature include statistics on predilection for sex and location. As recently as 1996, a marked female predominance was reported.20 In contrast, our review suggests only a slight predominance (56% female versus 44% male). Thoracic calcifications have been reported as more common than lumbar disease,20,30,34 but we found cases more equally distributed between the two regions (thoracic, 52%; lumbar, 48%). Again, the differences between our study and other reports may reflect available cases or other exclusion criteria. In particular, autopsy series showed a relatively high incidence of asymptomatic calcifications in the thoracic spine.

Presentation and Origin of Arachnoiditis Ossificans

The symptoms of thoracic disease include lower back pain, leg weakness, myelopathy, and signs of spinal cord compression syndrome. With lumbosacral disease, lower back pain, radicular signs with leg pain, sensory disturbances, and bowel and bladder disturbances can occur. Neurological deficits depend on the size, location, and morphology of the calcifications. In the thoracic spine, the calcifications have been described as ossified plaques or as cylindrical (surrounding the spinal cord). In the lumbar spine, the calcifications have been described as columnar, cylindrical, or irregularly shaped masses.10

Although the exact etiology of arachnoiditis ossificans is unknown, several factors may predispose an individual to develop the disease. Previous spinal surgery, spinal trauma, subarachnoid hemorrhage (e.g., from a vascular malformation or tumor), thecal puncture with or without the administration of contrast agents or drugs, and infection are the major factors that have been implicated. Some cases are idiopathic. No association between calcifications and systemic abnormalities of calcium metabolism has been discovered.39

The exact mechanism for the pathogenesis of these calcifications remains speculative. Ossification related to hemorrhage is likely if the patient’s medical history is consistent. Ossification can also be degenerative and occur in small foci of meningothelial proliferation.6Autopsy reports regarding the location and distribution of the calcifications support this theory. Arachnoidal cells are multipotent and found in increased numbers in the thoracic area.34 Metaplasia may lead to the proliferation of osteoblasts and, hence, to the development of ossification.34 Asymptomatic, diffuse calcifications may be due to this meningothelial degeneration, while focal, symptomatic arachnoiditis ossificans may be related to heterotopic bone from a previous irritant.

Diagnosis

Arachnoiditis ossificans is difficult to diagnose because the current evaluation for back pain relies on MR imaging and CT myelography. MR imaging does not image bone optimally, but it can be helpful in excluding other etiologies such as stenosis of the spinal canal or a compressive mass. CT myelography often obscures the findings since the densities of bone and intrathecal contrast are similar. Myelography has even been described as misleading and nondiagnostic for arachnoiditis ossificans.4 The spinal canal may appear to be patent on myelographic studies when, in fact, it is severely compromised by a mass of calcified intradural bone.

Calcifications should be diagnosed and delineated by basic CT. The value of noncontrast CT in this disease is well-described. The difference between the attenuation coefficients for cerebrospinal fluid and calcification is high, thus demonstrating the calcifications. Furthermore, associated arachnoiditis is often visible.1,8,20,28,29

Treatment Outcomes

What conclusions can be drawn from the literature and case report data? First, it should be stated that the available numbers are too few to achieve a reliable and valid statistical significance. However, it is clear that most patients (37 of 44 or 84%) received surgical treatment, and 87% (32/37) of these patients either improved (22/37 or 60%) or their symptoms were unchanged (10/37 or 27%). Thus, surgery should be considered in every case of arachnoiditis ossificans. It is quite likely, however, that many cases with poor surgical outcomes have never been published. This number is impossible to estimate but would impose a definite selection bias on this review.

Patients with thoracic lesions may tend to fare better after surgery than those with lumbar arachnoiditis ossificans because neurologic deficits from lesions that compromise the spinal cord, including the conus medullaris, would appear to have a high probability of improving after decompressive surgery. In many of the cases in the literature, the bony mass adhered to the inner surface of the dura but was easily peeled away from the pia mater and successfully removed, with decompression of the spinal cord.

Thus, the level of disease (thoracic versus lumbar) may be an important factor in determining the efficacy of surgery. All of the cases of lumbar arachnoiditis ossificans involved the cauda equina, where the density of traversing nerve roots is high. Sometimes, cauda equina lesions are shell-like and easily removed. When, however, the calcification is intertwined with the nerve roots, surgery becomes much more difficult. The chances of a good recovery may be less optimistic, and the risk of the patient’s neurologic condition worsening after surgery may be higher. The available data also indicate that five of the six patients who did not undergo surgery had lumbar arachnoiditis ossificans.

Surgery itself can further enhance the arachnoiditis, and multiple surgeries are often needed because of extension of the ossific plaque.29 It is not the goal of surgery to remove the entirety of the calcifications. Rather, multiple surgeries are often needed to relieve the compression adequately. For example, Toribatake et al.34 related a patient’s long-term improvement after two separate decompressive surgeries without removal of the mass. One author states that attempts to remove the ossific plaques from the surface of the spinal cord, conus medullaris, or cauda equina should be avoided.20 Postoperative complications include neurogenic bowel and bladder dysfunction as well as motor and sensory deficits.

Management of patients with arachnoiditis ossificans has also included medical therapies. Shiraishi et al.29 used low-dose aspirin to improve local blood circulation, but the efficacy of this treatment is unknown. Steroid therapy, however, is neither helpful nor indicated for this disease.29 The indications for intraspinal steroids are complex and controversial and have been discussed extensively elsewhere.19 Physical therapy plays a vital role in the patient’s postoperative management.29

Indications

Unfortunately, the indications for surgery remain unclear. Compression of the spinal cord or cauda equina from a calcified mass seems the only clear indication, but its removal does not guarantee that symptoms will improve.15,33 Reasons to decline surgery seem obvious if the patient only complains of mild symptoms. Small, fine calcifications have been declined for surgery too8 (our case). However, removal of calcific plaque adherent to the cauda equina has proven successful.37 Another case with involvement of the cauda equina showed improved sensory but not motor or vesicorectal function.10 At this point, the strongest conclusions that can be made from the published cases are that most patients with arachnoiditis ossificans do go to surgery (84%) and most of these patients improve (60%) or remain stable (27%).

Recommendations

Before surgery, it is important to describe the location, appearance, and distribution of the spinal calcifications. The need for surgery depends upon these factors and their contribution to spinal cord compression. Adequate surgical decompression can be obtained with thoracic disease, often after multiple surgeries. In contrast, surgery seems less likely to be of benefit when the disease involves the cauda equina and lumbar spine. Future articles on arachnoiditis ossificans should include information regarding medical management and its success, the imaging modalities used, and their contribution to the diagnosis.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Drs. Volker K. H. Sonntag and Ernesto Coscarella for translating articles in German and Italian, respectively.

References

- Barthelemy CR: Arachnoiditis ossificans. J Comput Assist Tomogr 6:809-811, 1982

- Bianchi-Maiocchi A: Un raro caso di calcificazioni diffuse dell’ aracnoide spinale (aracnoidite calcarea). Arch Ortop (Milano) 68:629-639, 1955

- Carbone F, Hasaerts R, Cordier J: Ossification diffuse de l’aracnoide spinale. Acta Neurol Belg 54:183-191, 1954

- Dennis MD, Altschuler E, Glenn W, et al: Arachnoiditis ossificans. A case report diagnosed with computerized axial tomography.Spine 8:115-117, 1983

- Gatzke LD, Dodge HW, Jr., Dockerty MB: Arachnoiditis ossificans. Report of two cases. Mayo Clin Proc 32:698-704, 1957

- Gulati DR, Bhandari YS, Markland ON: Spinal arachnoiditis ossificans. Neurol India 13:196-198, 1965

- Herren RY: Occurrence and distribution of calcified plaques in the spinal arachnoid in man. Arch Neurol Psychiatry 41:1180-1186, 1936

- Jaspan T, Preston BJ, Mulholland RC, et al: The CT appearances of arachnoiditis ossificans. Spine 15:148-151, 1990

- Kaufman AB, Dunsmore RH: Clinicopathological considerations in spinal meningeal calcification and ossification. Neurology 21:1243-1248, 1971

- Kitigawa H, Kanamori M, Tatezaki S, et al: Multiple spinal ossified arachnoiditis. A case report. Spine 15:1236-1238, 1990

- Knoblich R, Olsen BS: Calcified and ossified plaques of the spinal arachnoid membranes. J Neurosurg 25:275-279, 1966

- Lynch C, Moraes GP: Spinal arachnoiditis ossificans: Case report. Neurosurgery 12:321-324, 1983

- McCulloch GAJ: Arachnoid calcification producing spinal cord compression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 38:1059-1062, 1975

- Miles J, Bhandari YS: Ossifying spinal arachnoiditis. Neurochirurgia(Stuttg) 14:184-188, 1971

- Morello A, Nastasi G, Mangione G: Aracnoidite ossificante e metaplasia ossea dell’ aracnoide. Acta Neurol (Napoli) 22:787-795, 1967

- Motoe S, Itoh T, Noguchi T, et al. A rare case of paraplegia due to arachnoiditis ossificans and spinal osteochondroma in a patient with incomplete Marfan’s syndrome (in Japanese). Rinsho Seikeigeka 16:689-694, 1981

- Nagpal RD, Gokhale SD, Parikh VR: Ossification of spinal arachnoid with unrelated syringomyelia. Case report. J Neurosurg 42:222-225, 1975

- Nainkin L: Arachnoiditis ossificans. Report of a case. Spine 3:83-86, 1978

- Nelson DA: Intraspinal therapy using methylprednisolone acetate. Twenty-three years of clinical controversy. Spine 18:278-286, 1993

- Ng P, Lorentz I, Soo YS: Arachnoiditis ossificans of the cauda equina demonstrated on computed tomography scanogram. A case report. Spine 21:2504-2507, 1996

- Nizzoli V, Testa C: A case of calcification in the spinal arachnoid giving rise to spinal cord compression. J Neurol Sci 7:381-384, 1968

- O’Rourke DM, Simeone FA: Subacute onset of thoracic myelopathy secondary to compressive posterior osseous anomaly. Case report. Spine 16:990-991, 1991

- Ochiai H, Furuse K, Imakiue A, et al: A case of arachnoiditis ossificans with cord compression of thoracic spine region (in Japanese). Seikeigeka 31:371-376, 1981

- Pomerance A: Spinal arachnoiditis ossificans. J Path Bact 87:421-423, 1964

- Puusepp L: Surgical intervention in four cases of myelitis compression caused by osseous deposits in the arachnoidea of the spinal cord (arachnoiditis ossificans). J Nerv Ment Dis 73:1-19, 1931

- Quiles M, Marchisello PJ, Tsairis P: Lumbar adhesive arachnoiditis. Etiologic and pathologic aspects. Spine 3:45-50, 1978

- Schild H, Menke W, Kuhn FP: Arachnoiditis ossificans der LWS. Rontgen-Bl 36:158-159, 1983

- Sefczek RJ, Deeb ZL: Case report: Computed tomography findings in spinal arachnoiditis ossificans. J Comput Tomogr 7:315-318, 1983

- Shiraishi T, Crock HV, Reynolds A: Spinal arachnoiditis ossificans. Observations on its investigation and treatment. Eur Spine J 4:60-63, 1995

- Slager UT: Arachnoiditis ossificans. Report of a case and review of the subject. Arch Pathol 70:322-327, 1960

- Soloview VN: Changes in the spinal cord in the so-called spinal ossificating arachnoiditis. Arch Pathol 35:48-54, 1973

- Tanaka K, Nishiura I, Koyama T: Arachnoiditis ossificans after repeated myelographies and spinal operations—a case report and review of the literature. No Shinkei Geka 15:89-93, 1987

- Tetsworth KD, Ferguson RL: Arachnoiditis ossificans of the cauda equina. A case report. Spine 11:765-766, 1986

- Toribatake Y, Baba H, Maezawa Y, et al: Symptomatic arachnoiditis ossificans of the thoracic spine. Case report. Paraplegia 33:224-227, 1995

- Tsuruta T, Kato K, Matsuike H, et al: Case of arachnoiditis [Japanese]. Seikei Geka 20:1571-1575, 1969

- Van Paesschen W, Van den Kerchove M, Appel B, et al: Arachnoiditis ossificans with arachnoid cyst after cranial tuberculous meningitis. Neurology 40:714-716, 1990

- Varughese G: Lumbosacral intradural periradicular ossification. Case report. J Neurosurg 49:132-137, 1978

- Verbiest H: Neurogenic Intermittent Claudication. New York: Elsevier: 1976

- Whittle IR, Dorsch NW, Segelov JN: Symptomatic arachnoiditis ossificans. Report of two cases. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 65:207-216, 1982

- Wise BL, Smith M: Spinal arachnoiditis ossificans. Arch Neurol 13:391-394, 1965

- Zanda L: Ueber die Entwichlung der Osteome der Arachnoidea spinalis. Beitr Pathol Anat 5:393-400, 1889