Preparing Patients for Possible Neuropsychological Consequences After Brain Surgery

Author

George P. Prigatano, PhD

Division of Neurology, Barrow Neurological Institute, St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center, Phoenix, Arizona

Abstract

Patients who have a successful outcome after neurosurgery may still experience residual neuropsychological symptoms that may be subtle to the examiner but devastating to the patient. Over the years, many patients have expressed the opinion that some discussion of such possible sequelae before surgery would have been helpful to them. This article documents one patient’s eloquent statement about this issue. It also reports an informal survey that queried neurosurgeons about whether they routinely discuss possible neurological sequelae with patients before brain surgery. Providing patients with a simple brochure describing possible temporary or long-term neuropsychological consequences is suggested. Such information must be shared in a manner that does not frighten or upset the patient but that provides true informed consent.

Key Words : neuropsychology, neurosurgery, patient education

Ethical and legal mandates require neurosurgeons to discuss with patients possible mortality and morbidity risk factors when proposing neurosurgery. Typically, the morbidity factors are limited to those observed on neurological examination. Many patients, however, may experience residual neuropsychological disturbances not easily detected by examining physicians but nevertheless of substantial importance to the patient.

These disturbances can be varied and include subtle, but important, changes in a patient’s capacity to remember new information, express his or her ideas in words, maintain a logical trend of thought, solve abstract reasoning problems, and perceive objects clearly and accurately. Patients also may experience alterations in their energy level, and some complain of considerable “mental fatigue” even when carrying out routine mental tasks such as reading a newspaper.2

No prospective study has documented the temporary and sometimes permanent neuropsychological sequelae of elective brain surgery for such focal lesions as cerebral aneurysms or arteriovenous malformations. Existing literature suggests, however, that in cases of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) and “early operation,” neuropsychological disturbances may be noted several months and years after surgery in some patients who otherwise have good neurological recoveries.

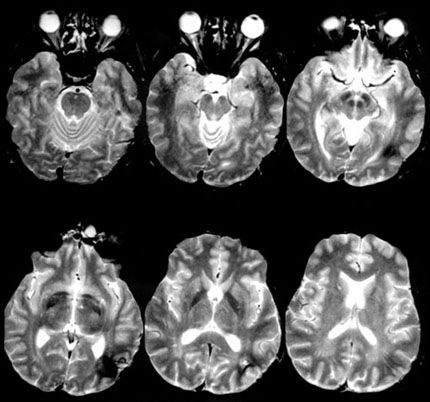

Figure 1. Preoperative axial magnetic resonance images show patient’s left parieto-occipital cavernous malformation. Surgical removal of the lesion left the patient with subtle neuropsychological deficits that he had not expected.

For example, Ljunggren and coworkers3 studied the long-term outcome of a randomly selected group of 40 such patients 14 months to 7 years after surgery (mean chronicity, 3.5 years). Lesion locations varied. Patients were interviewed clinically and given a variety of psychometric tests. Thirty percent experienced a permanent sense of fatigue and lack of initiative, 57.5% reported memory disturbances, and 83%, as measured by psychometric tests, demonstrated learning and memory deficits. Seventy percent (70%) reported difficulties in emotional adjustment that had not existed before SAH and surgery. Maurice-Williams and coworkers4 also noted that only 44% of 27 patients were free of psychological symptoms after successful operations of Grade 1 and 2 ruptured intracranial aneurysms. Neuropsychological disturbances were not always detected by standard psychometric tests. These findings suggest that neuropsychological disturbance may be more common than is typically anticipated if an operation is deemed a success based purely on neurological criteria.

Preparing Patients for Possible Neuropsychological Deficits

Undoubtedly, patients about to undergo brain surgery are preoccupied by the possibility of dying or of having significant paralysis as a result of an operation. At such times, it may seem unkind and even irresponsible to worry them about possible neuropsychological sequelae. Yet, some articulate patients have noted that they were totally unprepared for subtle but important neuropsychological disturbances that they experienced after their surgery and would have preferred having as much information as possible about the potential neuropsychological consequences of any procedure, regardless of how expertly performed. A case example highlights this point.

Illustrative Case

A 37-year-old man underwent a craniotomy to remove a left parietooccipital cavernous malformation (Fig. 1). The patient was a successful businessman and had his private pilot license. His surgery was uneventful and he experienced no complications.

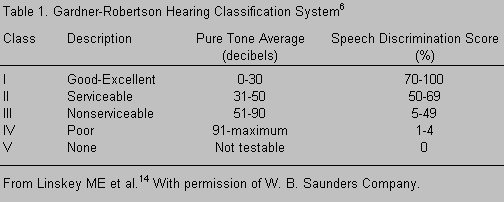

About 1 month after surgery he underwent a neuropsychological examination because of reported subtle language and memory difficulties. He demonstrated average-to-bright normal intelligence with no obvious intellectual impairment. Yet, his intelligence quotient (IQ) scores (Table 1) suggested a general disruption of function. While his IQ values were in the normal range, he had functioned in the above average range before surgery. His verbal learning score was 1.5 standard deviations below average. His speed of information processing was compromised substantially (Digit Symbol subtest = 7). His visual-spatial problem-solving skills appeared to be above average (Block Design subtest = 12), but he was less able to solve higher order visual-spatial tasks than before surgery. He also noted that he could easily recognize objects, but something was indescribably different about them. As a pilot, he described his visual-spatial condition as reflecting an impairment in vision that was about “5Þ off the magnetic North.”

Because this patient was such an articulate spokesman about not fully having appreciated the potential sequelae of his surgery, I asked him to write about his experiences after the operation. He had the following to say:

On May 10, 1994 I had a craniotomy of the left parietal occipital region for a cavernous malformation. Everything happened in quick fashion prior to that. An episode of amnesia, a possible seizure at work (no one knows, I was in a remote warehouse at the time), several hours bumbling around in my office not fully comprehending nor being able to communicate adequately with other people. My adept office staff never caught on. Thankfully, someone from outside the office thought I had acted strange and pressured my absent boss to take me to my doctor. The doctor ordered magnetic resonance (MR) imaging which revealed a malformation that had bled or was bleeding. A top-notch neurosurgeon from an acclaimed institution was enlisted, rather quickly I might add, to conduct surgery. Eight days later in the intensive care unit my neurosurgeon was extremely pleased with how things were going and full recovery was to be expected.

Four days later I was home and obviously a little giddy about having dodged a big bullet. Everything seemed to be right on track. Heal up a little, go back to work, and forget that this bad dream ever happened. This was my thinking anyway, until six days postoperative my wife asked me what I was doing. My response was a total blank! I had a complete inability to express in words what I was doing! I stood stunned for a bit, then turned away quickly so she wouldn’t notice the tears.

Let me preface my experience by saying how grateful I am to be alive and functional. The gratitude I have for my doctors in the speed, skill, and professional manner in which they acted is a real tribute to the medical community. I’m still amazed how such a delicate organ as the brain can be taken for granted, when even a slight malfunction can be the difference between life and death. Thankful? You bet! My sons, hopefully, when they’re older and able to understand what happened to Dad will be thankful. My wife, too. This experience has elevated us to a whole new level in our relationship. One that I hope will keep us bonded forever.

Having said all that, let me tell you why I’m angry. Angry at you!

When I was told I would need surgery, my neurosurgeon was of course very matter-of-fact. The malformation was very reachable and there was no need to be too concerned. The downside was a 3% chance of death and a 5% chance of some type of therapy being needed.

“Alright, death,” I said to myself, ‘that’s everyone’s ultimate concern.”

“Therapy, well I can do that. A couple of sessions of leg lifts, a few bicep curls, maybe come whirlpool time and presto! I’ll be good as new!”

There was no way I could have even imagined the actual inability to either comprehend or communicate with anything less than I had ever had before. No attempt, other than a few stats, was ever mentioned to me about what a real life experience might be like. Turning numbers around, difficulty in reading, complete memory lapses and tedious tasks? Forget it! Perhaps I should count my blessings considering the state other patients are in. Perhaps. But just perhaps my pain is no less heartfelt than those of others. What I wanted was an informed decision prior to surgery. The outcome would’ve been the same but with a hell of a lot less agony.

I was later diagnosed by a neuropsychologist as having a slight but classical left parietal occipital dysfunction. I accept that. I’m taking therapy for that. I can cope with that. That’s life. What I’m really angry about is the veil of darkness that looms over the medical community for mental preparedness of brain patients. A simple list with possible side effects is the least that I feel is needed. Better yet, a preoperative consultation as to what may happen would be valuable. The surgeon, on the other hand, measures success differently than the patient. After all I am whole with no noticeable side effects. But should you not treat the whole person? I went to birthing classes for my children. How about brain classes before surgery?

Neurologists too, seem to have difficulty in treating the whole person. Picture the difficulty of not only having to battle the effects of surgery but also of antiseizure drugs. In the real world we cannot skip work. We must work. Trying to function under these circumstances is trying at best, but having to battle the side effects of [drug name deleted] is almost impossible. What is the obsession you guys have with [drug name deleted]?? I tried for sometime to get off that drug on to a substitute but could never get my message across to my neurologist. How do you describe a heretofore undiscovered sensation? Out-of-sync, out-of-body, electrodes to the brain? I’m not sure. What’s the side effect of the drug vs. surgery? Perhaps a little depression too? It’s hard to delineate all of the combinations. So I quit the drug. Had a seizure several months later, had to go back on [drug name deleted], felt the same sensations, realized it was the drug and whined enough to my neurologist till he put me on [drug name deleted]. I feel better now. I still feel like I’m on medication but it’s bearable and preferable to what I was experiencing. Those horrible feelings of [drug name deleted] and the prospect of life on it gave me for the first time in my life sympathy for someone who commits suicide. Yes, it was that bad.

In conclusion, I want for all of you to know that I truly want a constructive change in how brain patients are treated, as well as informed prior to surgery. I am not a complainer. I can bear pain when it is necessary. However, to alter one’s reality without so much as a hint is, I feel, pretty cruel.

Methods

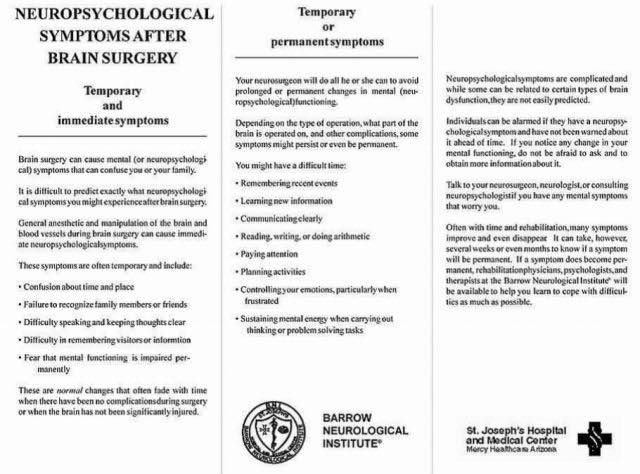

Over the years other patients have shared similar concerns. Their comments have questioned if patients are prepared adequately for subtle but important neuropsychological deficits after neurosurgery. I therefore informally surveyed neurosurgical colleagues to determine if they typically discuss the potential neuropsychological consequences of brain surgery with their patients. Twenty neurosurgeons received a letter asking them to respond to a brief questionnaire after reading two case scenarios (Fig. 2). Of the 20 neurosurgeons, 11 practice in Phoenix, Arizona; 6 in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma; 2 in Tulsa, Oklahoma; and 1 in San Diego, California.

Results

Thirteen (65%) of the questionnaires were returned. Six (46.2%) responded that they routinely review with patients the possible neuropsychological sequelae after surgery for a brain tumor, arteriovenous malformation, or aneurysm; five (38.4%) did not. Two (15.4%) responded, “It depends.”

In answer to the second question concerning what neuropsychological deficits might be expected with surgical resection of an arteriovenous malformation (AVM), 10 of the 13 neurosurgeons identified possible language impairment and 3 identified possible difficulties with reading and writing. Of the 13 replies, one noted that such patients might have difficulties following conversations. One neurosurgeon mentioned memory impairment and one mentioned spatial perceptual deficits. None of the neurosurgeons mentioned the potential problem of anomia and the loss of normal thought patterns.

In answer to the third question about a temporal lobectomy, 8 of the 13 neurosurgeons suggested that memory impairments were common after an anterior temporal lobectomy. One suggested the possibility of difficulties in abstract thought or the ability to sequence one’s thoughts in a logical manner. Two suggested possible subtle perceptual deficits, and three suggested possible personality changes. Three stated that they would expect no deficits.

Discussion

The neurosurgeons sampled were far from a random sample of neurosurgeons in the United States. All respondents represented neurosurgeons with whom I had worked professionally. They were therefore used to considering neuropsychological sequelae after brain surgery. Neurosurgeons who do not typically refer patients to neuropsychologists would likely discuss possible neuropsychological sequelae with their patients even less frequently.

The results of this informal survey further suggest that patients may need more information about the possible consequences of their brain surgery. For example, only three surgeons identified difficulties with reading and writing as sequelae to resection of an AVM in the left occipitoparietal region. Given the location of the lesion in that area and its proximity to the splenium of the corpus callosum, however, reading difficulties are common for such patients. Furthermore, only one surgeon listed difficulty following conversations as a potential problem after such surgery. The patient reported here, however, perceived this defect as a major problem. And, in my experience, this issue has been a major challenge for many patients with left hemisphere lesions, particularly when the occipitoparietal region is involved.

Memory impairments also are quite common after any lesion of the brain.1 Often, however, neurosurgeons may feel that memory will only be impaired substantially if deep brain structures have been affected. This is clearly not the case. The patient presented here was very distressed by his anomia and disrupted thought patterns, and neither deficit was mentioned by any of the neurosurgeons polled.

Numerous patients also exhibit difficulties in abstract thought and logical sequencing. Recently, for example, a young woman underwent a successful anterior right temporal lobectomy to control her seizures. She was extremely happy with the outcome of surgery but confused because she seemed to have some neuropsychological impairments that she had not noticed before her surgery. Because her psychometric test scores showed no change, she wondered if these impairments were imagined or real. Talking with her revealed that her speed of information processing was reduced and that she had problems with sequencing her thoughts and with her memory. Neuropsychological tests often do not capture important changes in a patient and to rely solely on test findings without taking a careful history would be a tremendous mistake in evaluating these patients.

It would be extremely difficult for most people to imagine what it would be like to experience these kinds of changes in higher cerebral functioning. Very few experiences in our daily life prepare us to describe the changes in neuropsychological functioning that can accompany these surgeries. Consequently, it is extremely important that information be given to patients routinely to help them cope with possible neuropsychological sequelae after both elective and nonelective brain surgery.

The available evidence suggests that it would be appropriate to provide patients with information about the potential neuropsychological consequences after surgery for various brain lesions. A simple brochure (Appendix) would serve the purpose of informing patients that they might experience temporary deficits that could be frightening and upsetting. It is important for patients and their families to know that such changes may be normal and often disappear. More long-lasting problems and the possibility that they might be permanent also are mentioned. When discussing this delicate issue, the choice of wording is crucial. The wording developed here is intended to inform without overwhelming the patient.

Such a brochure could be given to patients at the time of neurosurgical consultation, but obviously the attending neurosurgeon would share the information based on his or her clinical judgment. In some instances, certainly not all, a presurgical discussion of possible neuropsychological deficits with an experienced clinical neuropsychologist also might be helpful.

Because no prospective studies have examined the immediate and long-term consequences of elective brain surgery, we are about to undertake such a study. Sensitive as well as sensible tests of higher cerebral functioning might differentiate temporary and permanent neuropsychological sequelae. The goal is to provide patients with information in the event that neuropsychological consequences occur. Fortunately, many patients who undergo elective brain surgery show minimal, if any, sequelae. The point is not to alarm patients unnecessarily but to give them and their family potentially useful information. The eloquence of the patient’s testimony reported here attests to this need. It is hoped that by increasing awareness about this issue, not only the medical and surgical needs of our patients can be addressed, but their psychological needs as well.

References

- Baddeley AD, Wilson BA, Watts FN (eds): Handbook of Memory Disorders. West Sussex, England, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd:1995

- Brodal A: Self-observations and neuro-anatomical considerations after a stroke. Brain 96: 675-694, 1973

- Ljunggren B, Sonesson B, Saveland H, et al: Cognitive impairment and adjustment in patients without neurological deficits after aneurysmal SAH and early operation. J Neurosurg 62: 673-679, 1985

- Maurice-Williams RS, Willison JR, and Hatfield R: The cognitive and psychological sequelae of uncomplicated aneurysm surgery. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 54: 335-340, 1991