Hemangiopericytoma of the Parasellar Region: Case Report and Review of the Literature

Sam Safavi-Abbasi, MD, PhD

Iman Feiz-Erfan, MD

Ruth E. Bristol, MD

William L. White, MD

Division of Neurological Surgery, Barrow Neurological Institute, St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center, Phoenix, Arizona

Abstract

We present a patient with a hemangiopericytoma of the parasellar region and briefly review the literature. Differentiation of this rare and challenging lesion from a meningioma is crucial because the former has the poorer prognosis. Hemangiopericytomas are thought to be best treated with aggressive resection followed by radiation.

Key Words: hemangiopericytoma, radiosurgery, sella, transsphenoidal approach

Abbreviations used: CNS, central nervous system; CT, computed tomography; GKRS, Gamma Knife radiosurgery; MR, magnetic resonance

Historically, hemangiopericytomas have been grouped with meningiomas and described as vascular forms of these tumors.[4] They are postulated to arise from meningeal capillary pericytes or precursor cells with angioblastic tendencies, but they also can develop without a meningeal component.[2,4] Hemangiopericytomas are considered to be aggressive neoplasms that can occur anywhere in the body. They are found in all age groups and exhibit a slight male predominance.[2,4,5,9]

Primary hemangiopericytomas of the CNS are rare tumors. Their incidence is less than 1% of primary intracranial neoplasms.[4] Like meningiomas, hemangiopericytomas are commonly found in the parasagittal or falcine region.[4,5] Hemangiopericytomas of the sellar and parasellar region are extremely rare and account for only 1% of all primary intracranial hemangiopericytomas.[6-8,10,13] We report a patient with a parasellar hemangiopericytoma involving the sphenoid sinus and clivus with extension into the cavernous sinus.

Case Report

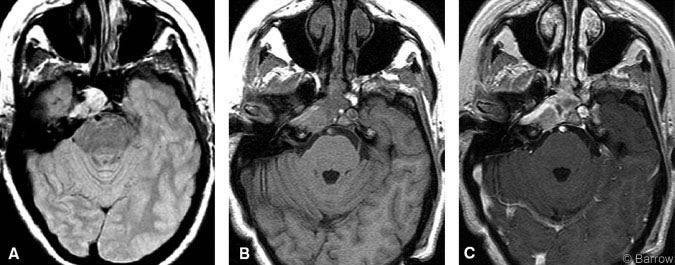

A 56-year-old Caucasian woman developed double vision 3 months before her admission. On examination, the patient demonstrated palsy of the right sixth cranial nerve. Otherwise, her cranial nerves were intact, and there was no evidence of visual field defects. Gait and tandem gait were performed with some difficulty. The remainder of her neurological examination was normal. MR imaging of the brain showed a 1.5-cm diameter parasellar mass involving the sphenoid sinus, clivus, cavernous sinus, and petrous apex (Fig. 1A). She underwent a transnasal endoscopic resection at an outside institution. A biopsy was performed, and the procedure was terminated due to excessive blood loss. The diagnosis based on pathological analysis was hemangiopericytoma. The patient was transferred to our institution for definitive management.

The tumor was accessed through a left transnasal-transseptal-transsphenoidal approach with fluoroscopic and neuronavigational guidance. A vascular, reddish-purple tumor was found primarily beneath the sella. The clivus and bony right lateral wall of the sphenoid sinus were eroded. The tumor approached the right optic nerve and right posteroinferior cavernous sinus and surrounded the posterior margins of the right internal carotid artery. The fibrotic pseudocapsule was opened. The fibrotic tissue was dissected from the normal cavernous sinus wall, and the tumoral components outside the cavernous sinus and within the sphenoid sinus were removed. Moderate bleeding was sufficiently controlled with bipolar cauterization and topically applied hemostatic agents.

Within months of surgery, the patient’s diplopia and movement of her right eye improved. She had no other neurologic complaints. Postoperative MR imaging showed total removal of the sphenoid sinus component with residual tumor behind the internal carotid artery in the petrous apex (Fig. 1B and C). Subsequently, she underwent GKRS.

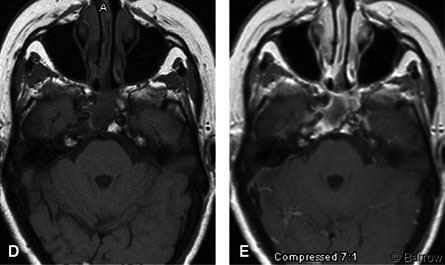

Three and a half years after surgery and radiosurgery, she is alive without evidence of disease progression. Her double vision has improved significantly, and she can again drive a car. The size of her residual tumor has shrunk (Fig. 1D and E).

Discussion

Historically, this tumor was confused with a variety of different neoplasms. [8] In their 1938 classification of meningiomas, Cushing and Eisenhardt[3] grouped hemangiopericytomas as one of three angioblastic, reticulinforming variants of meningiomas. Morphologic transitions between these tumors and microscopic foci of pericyte proliferation within otherwise typical meningiomas have been cited to support this relationship.[2] In 1942 Stout and Murray first described hemangiopericytomas as neoplasms of capillary pericytes and as separate pathological entities.[12] In 1954 Begg and Garret[3] reported the first case of intracranial hemangiopericytoma and reclassified three cases of angioblastic meningioma that had originally been reported by Cushing and Eisenhardt as hemangiopericytomas.[1] That most intracranial hemangiopericytomas arise from the meninges rather than from the brain parenchyma, where pericytes also exist, led to the term meningeal hemangiopericytoma. However, these tumors also occur in a pure form, without a meningeal component.[2]

It is now well accepted that both hemangiopericytomas and meningiomas arise from multipotential precursor cells.[4] The accumulation of data characterizing hemangiopericytomas with distinct ultrastructural, histological, and clinical properties has established these lesions as separate pathological entities.[4,8] Ultrastructurally, the presence of a basement membrane and the absence of desmosomal attachments distinguish hemangiopericytomas from meningiomas.[2,4]

Histologically, hemangiopericytomas are extremely vascular with a characteristic arrangement of tumor cells outside the sheaths of vascular channels. This pattern is seen best after reticulin staining.[2,4] In hemangiopericytomas, reticulin envelops the individual cell whereas in meningiomas reticulin envelops cell groups.[4] Regardless of how these tumors are categorized, their malignant behavior has long been recognized as distinct from the behavior of meningiomas.

Hemangiopericytomas are usually found in adults. Compared to meningiomas, hemangiopericytomas occur more often in males at an earlier age, grow more rapidly, and tend to recur and metastasize more often, frequently outside the CNS.[4] In decreasing order of frequency, the most common sites of metastasis are bone, liver, lung, abdominal cavity, the CNS, and meninges.[9] These tumors can occur throughout the CNS, but like meningiomas they are more often found in falcine or parasagittal locations.[5] Unlike meningiomas, primary multifocal hemangioblastomas have not been reported.[4]

Sellar, suprasellar, and parasellar hemangiopericytomas are extremely rare. To our knowledge, only five cases have been reported.[6-8,10,13] Between 1938 and 1987, Guthrie and coworkers studied 44 cases of intracranial hemangiopericytomas, only two of which were in the sellar and suprasellar region, respectively.[5]

Clinical Manifestations

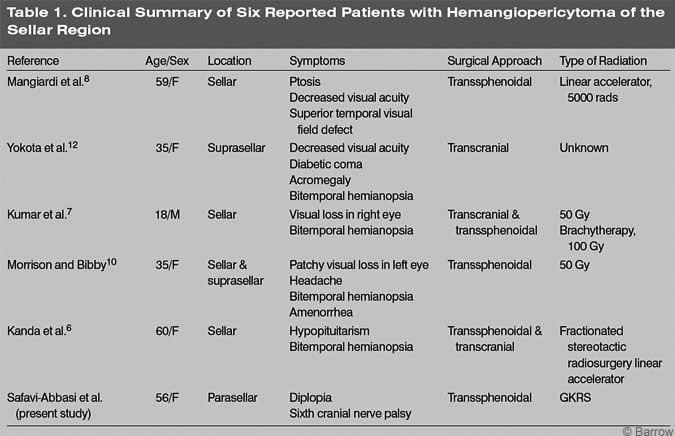

Sellar and parasellar hemangiopericytomas can mimic pituitary adenomas. In 1983 Mangiardi and coworkers reported the first case of a hemangiopericytoma involving the pituitary fossa.[8] The patient became symptomatic with headache and rapid visual loss (Table 1). Initially, this patient’s presenting symptoms and preoperative findings were attributed to a pituitary adenoma.

Visual decline has occurred in all reported cases. In four of the five known cases, bitemporal hemianopsia was the primary complaint (Table 1). Our patient’s only symptom was diplopia. Other symptoms reported to mimic pituitary adenomas are acromegaly, amenorrhea, and hypopituitarism (Table 1). Although intracranial hemangiopericytomas may be more common in men than in women, sellar lesions may predominate in the latter. On CT or MRI, it is difficult to differentiate intracranial hemangiopericytomas from other tumors, especially meningiomas.[4,5] The definitive diagnosis therefore remains histological.[4,5]

The treatment of choice for sellar hemangiopericytomas is surgical resection followed by radiotherapy. Because these tumors have a tendency to recur, every attempt should be made to achieve complete resection at the initial surgery. However, complete resection has been possible in only 50 to 70% of the cases.[4] In the sellar region, complete surgical resection can be difficult because these tumors have a tendency to extend and invade adjacent eloquent tissue. In our patient, the tumor eroded the right petrous apex, clivus, and sphenoid sinus and extended into the cavernous sinus. As in our case and in other reported cases, the carotid artery, optic nerve, and chiasm can also be involved.[6,7,13] The surgical approach depends on the exact location and extension of the tumor. A transsphenoidal approach has been used in four cases and a transcranial approach in three cases (Table 1).

Hemorrhage has been the limiting factor for complete resection.[6,10] In fact, this neoplasm has been reported to be richly vascularized contributing to significant rates of morbidity and mortality associated with surgical resection. However, improvements in operative techniques have decreased these high rates of surgical morbidity and mortality.[4] Still, the management of patients with intracranial hemangiopericytoma remains challenging and different factors affect prognosis.

Although hemangiopericytomas have a typical and distinct histological appearance, they are often misdiagnosed.[4] These neoplasms form discrete masses. As in our patient, however, the lesions can invade and destroy adjacent bone.[2] The aggressive biological behavior of these tumors is another factor that limits treatment.

The 15-year overall survival and recurrence rates for hemangiopericytomas have been reported to be 43 and 87%, respectively.[4,11] More often than any other primary intracranial neoplasms, hemangiopericytomas tend to metastasize outside the CNS. The mean length of survival after metastasis is reported to be 24 months.[4] Age, sex, and histology are not factors that contribute to the outcome of postoperative radiation.[4] Statistically, the most important factor contributing to outcome is postoperative radiation.[4,5]

Radiation therapy has been included in the treatment of almost all sellar hemangiopericytomas (Table 1). In fact, postoperative radiation of at least 5000 to 5500 cGy decreases the probability of recurrence.[4] However, very different techniques have been used for postoperative radiotherapy of sellar hemangiopericytomas (Table 1). Radiosurgery has been used to treat inoperable meningiomas, and it is considered to be effective for the treatment of unresectable hemangioblastomas.[4] Because complete resection of the tumor was impossible in our patient, we decided to treat her postoperatively with GKRS. Three and a half years after therapy, she has shown no evidence of disease progression.

Conclusion

Hemangiopericytomas are aggressive tumors that tend to recur and metastasize. In the sellar and parasellar regions, these tumors can mimic the signs and symptoms of pituitary adenomas. When complete surgical resection in this location is infeasible because of hemorrhage or because the tumor extends into adjacent structures, postoperative radiotherapy is mandatory.

References

Begg CF, Garret R: Hemangiopericytoma occurring in the meninges: Case report. Cancer 7:602-606, 1954

Burger PC, Scheithauer BW: Tumors of the Central Nervous System. Washington, DC: American Registry of Pathology, 1993

Cushing H, Eisenhardt L: Meningiomas: Their Classification, Regional Behavior, Life History, and Surgical End Results. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas, 1938

Guthrie BL: Meningeal hemangiopericytomas, in Kaye AH, Laws ER, Jr. (eds): Brain Tumors. An Encyclopedic Approach. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1995, pp 705-711

Guthrie BL, Ebersold MJ, Scheithauer BW, et al: Meningeal hemangiopericytoma: Histopathological features, treatment, and long-term followup of 44 cases. Neurosurgery 25:514-522, 1989

Kanda Y, Mase M, Aihara N, et al: Sellar hemangiopericytoma mimicking pituitary adenoma. Surg Neurol 55:113-115, 2001

Kumar PP, Good RR, Cox TA, et al: Reversal of visual impairment after interstitial irradiation of pituitary tumor. Neurosurgery 18:82-84, 1986

Mangiardi JR, Flamm ES, Cravioto H, et al: Hemangiopericytoma of the pituitary fossa: Case report. Neurosurgery 13:58-62, 1983

Mena H, Ribas JL, Pezeshkpour GH, et al: Hemangiopericytoma of the central nervous system: A review of 94 cases. Hum Pathol 22:84-91, 1991

Morrison DA, Bibby K: Sellar and suprasellar hemangiopericytoma mimicking pituitary adenoma. Arch Ophthalmol 115:1201-1203, 1997

Soyuer-S, Chang-EL, Selek-U, et al: Intracranial meningeal hemangiopericytoma: The role of radiotherapy:Report of 29 cases and review of the literature. Cancer 100:1491-1497, 2004

Stout AP, Murray MR: Hemangiopericytoma: A vascular tumor featuring Zimmermann’s pericyte. Ann Surg 116:26-33, 1942

Yokota M, Tani E, Maeda Y, et al: Acromegaly associated with suprasellar and pulmonary hemangiopericytomas. Case report. J Neurosurg 62:767-771, 1985