Dr. Michael T. Lawton’s Seven Takeaways from 5,000 Aneurysms

After more than two decades as a practicing neurosurgeon, Barrow President and CEO Dr. Michael T. Lawton has clipped his 5,000th aneurysm.

It’s a special milestone for Dr. Lawton, who is a crusader in the fight to preserve clipping as a brain aneurysm treatment option along with the increasingly popular endovascular techniques.

“Back when I trained as a resident, there was no option other than surgery,” he said. “Now, surgery is the less common option. I think, in some ways, open surgery is becoming a vanishing act.”

Dr. Lawton said the milestone also speaks to his ambition and dedication as a neurosurgeon, much like batting statistics measure the career of a baseball player.

“I’ve always viewed aneurysms kind of like hits in baseball and AVMs as home runs,” he said. “However you want to keep the stats, these are the things that define your successes, your commitments, and what kind of mark you want to make.”

In recognition of this extraordinary feat, we asked Dr. Lawton—author of the “Seven” series of neurosurgical textbooks including “Seven Aneurysms”—to share seven takeaways from treating these vascular abnormalities over the years.

1. Clipping aneurysms isn’t easy.

It is, after all, quite literally brain surgery. But Dr. Lawton explains that becoming a skilled aneurysm surgeon in particular takes many years of practice and perseverance.

“It’s like Malcolm Gladwell’s 10,000-hour rule; you have to do pretty much that to get good at this,” he said. “With that comes a lot of highs and lows, but by the time you reach 5,000, it’s a pretty awesome milestone. You’ve just got to keep at it.”

2. Teaching is the great multiplier.

When a scientist or physician invents a successful drug or vaccine, that individual can make an enormous impact in a short amount of time. Surgery is different, Dr. Lawton points out, because surgeons apply their craft one patient at a time. But he added that it’s important not to lose sight of the impact a surgeon can make over the course of their career. And when a surgeon trains future surgeons, that footprint is even larger.

“It’s that ripple effect,” he said. “That’s the beauty of teaching, it’s the beauty of being in an academic environment like Barrow, and it’s the beauty of having people listen. I’m lucky to have a platform where people listen.”

3. Every aneurysm is a challenge.

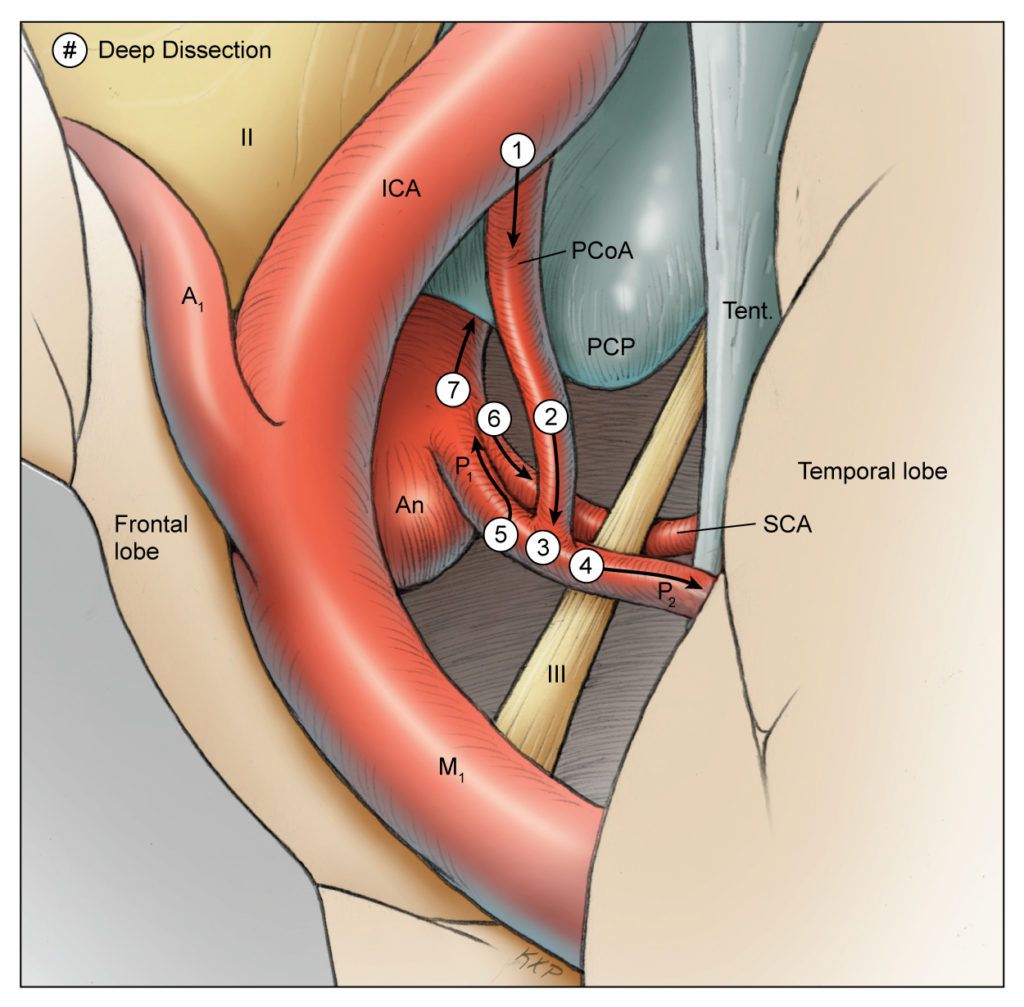

No two aneurysms are exactly the same, which is one of the reasons aneurysm surgery is so exhilarating, Dr. Lawton said. However, he noted that there is generally a gradient of difficulty.

“There are some aneurysms that are simpler and easier, and there are others that are difficult no matter what,” he said. “The one that stands out is the basilar apex aneurysm—the basilar bifurcation aneurysm. It’s deep, it’s unforgiving, and it forces you to do things where you can’t always see everything.”

4. Aneurysm clipping is a team sport.

Dr. Lawton shares this achievement with everyone he’s worked with in the operating room, including residents, fellows, scrub nurses, circulating nurses, neurophysiologists, and anesthesiologists.

“It’s wrong to take an accomplishment like this one and claim it as my personal success when it’s always been a team effort and you depend so heavily on all different pieces of the team,” he said.

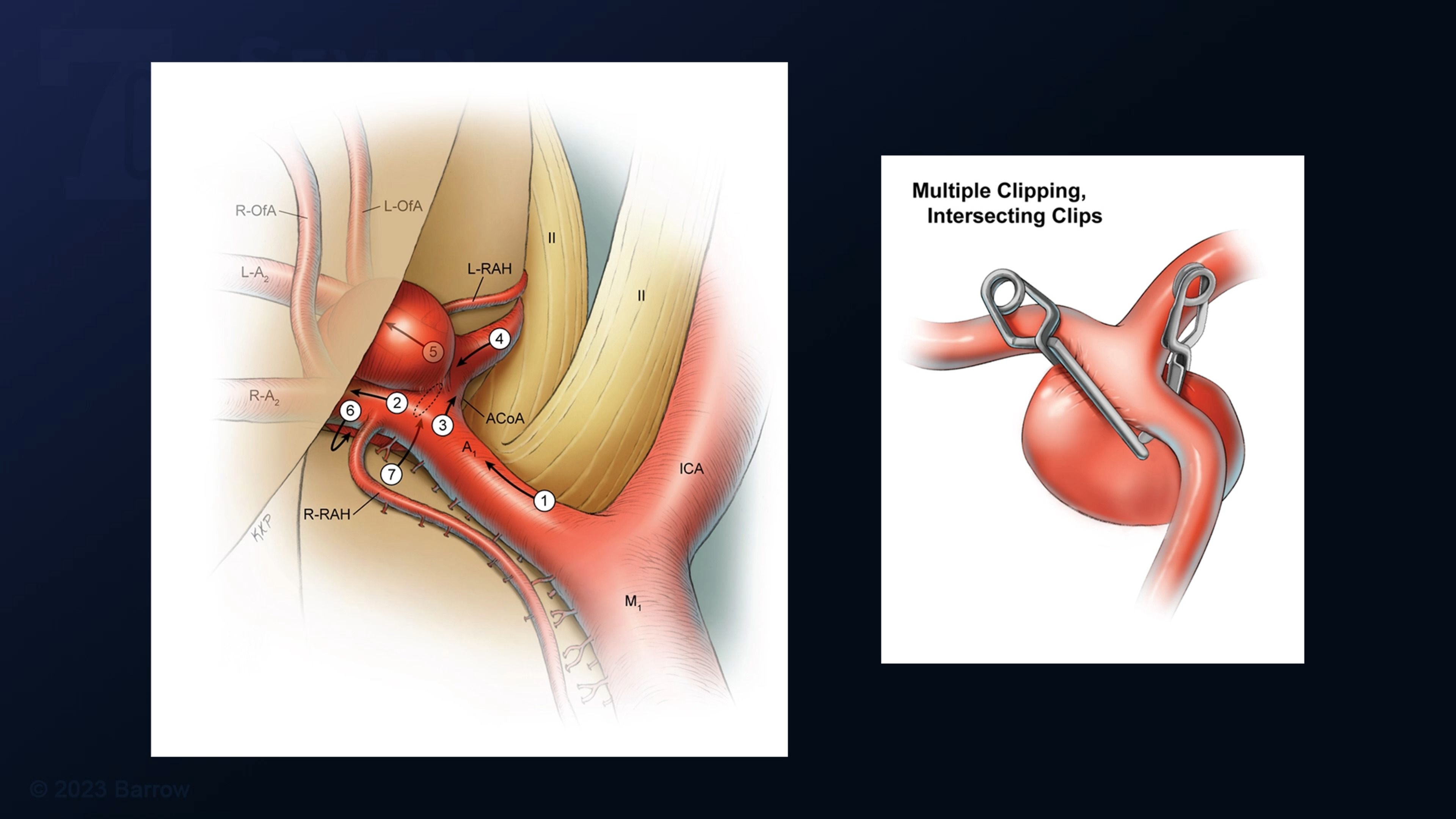

5. Aneurysm surgery can be choreographed.

Although each aneurysm can present different nuances and surprises, an aneurysm surgeon can generally follow a sequence of steps from beginning to end.

Dr. Lawton poeticized aneurysm surgery as the perfect tempo. “It sort of starts off easy, and it builds to this crescendo,” he said. “There’s this rising tension, this rising level of danger, and you get to that final act where you apply the clip, and then—in an instant—the pathology is cured. You can relax, and there’s this sort of denouement, and you finish the case.”

Dr. Lawton said this differs from arteriovenous malformation (AVM) surgery, which tends to be difficult from start to finish and which can draw surgeons into relentless battles. Aneurysm surgery is usually shorter, cleaner, and more elegant.

“I don’t know that I would give up one type of surgery for the other, but what I like about aneurysms is that—on a good day—I can do four aneurysm cases and be home for dinner,” he said.

There’s this rising tension, this rising level of danger, and you get to that final act where you apply the clip, and then—in an instant—the pathology is cured. You can relax, and there’s this sort of denouement, and you finish the case.

Dr. Michael Lawton

6. Overcoming bad outcomes takes healing, reflection, and redemption.

Sometimes the outcome isn’t what a surgeon expects or hopes for. Dr. Lawton compares these outcomes to wounds or injuries that must be mended.

“If there isn’t a period of healing, then it will weaken you and can really destroy you,” he warned. “You have to find ways to heal. I do that by having that time to reflect and pull something positive from it. That process of redemption is how you make it better. If you learn from it, then you pay it back in all those patients in the future where you avoid that complication or don’t make that mistake.”

7. Study every case ahead of time.

Before setting foot in the operating room, Dr. Lawton spends time reviewing each patient’s imaging to make sure he has a clear mental picture of the individual’s anatomy and pathology.

“It’s like forming a hypothesis and then finally confronting it, or studying a picture and then meeting the real person,” he said. “There’s a recognition; there’s a familiarity. You don’t want to have any surprises in there that you haven’t anticipated.”