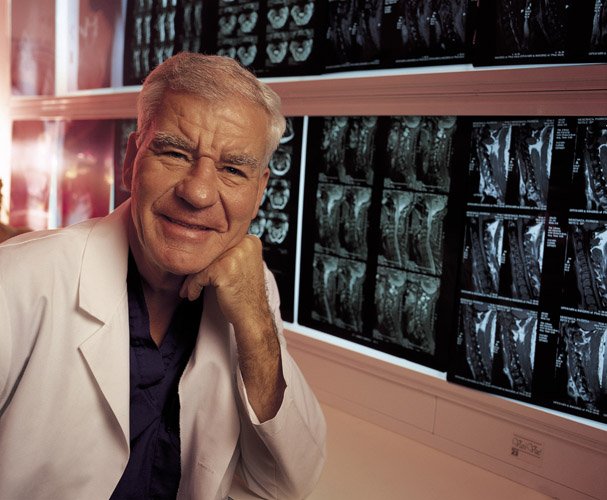

Q&A: Dr. Volker Sonntag, a Pioneer in Spinal Neurosurgery

When Dr. Volker Sonntag began practicing neurosurgery in 1977, spine specialists didn’t exist. Neurosurgeons treated the brain, spinal cord, and nerves. Surgeries involving the bones—especially those below the neck—belonged to orthopedic surgeons.

With few treatment options available for the spine, and neurosurgeons virtually limited to reducing pressure on the nerves, spine surgery lacked the influence of brain surgery. Dr. Sonntag performed spinal decompression surgeries to build his practice and pay the bills, traveling between Phoenix-area hospitals with his tackle box full of surgical tools.

Dr. Sonntag believed neurosurgeons should be able to treat the whole spine from the neck to the lower back, including the bony structures that encase the nerves. He gradually began performing spinal fusions with new instrumentation, such as rods, screws, and plates.

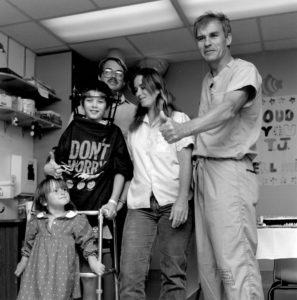

In our conversation in the Emeritus Suite at Barrow Neurological Institute, Dr. Sonntag tells the story of the turf wars that ensued between orthopedic and neurological surgeons. Behind him sits an old vise he purchased at Sears to bend his own rods—including the one he used in 1989 to reattach a 10-year-old boy’s skull to his spine after the ligaments connecting them were severed in a bicycle-truck accident.

A news story brought more controversy to Dr. Sonntag’s career when it claimed pedicle screws were dangerous and that surgeons were colluding with manufacturers. The claims were unfounded, the lawsuits dropped, and a review of Dr. Sonntag’s cases confirmed his success with instrumentation.

The American Board of Neurological Surgery added treatment by fusion and instrumentation to the definition of what a neurosurgeon does, and Dr. Sonntag is now recognized as a pioneer in spinal neurosurgery.

His journey is documented in a memoir called “Backbone: The Life and Game-Changing Career of a Spinal Neurosurgeon.” We sat down with him to talk about his contributions to the field and his experience with writing the book.

When did you realize you wanted to become a neurosurgeon?

It was my senior year in medical school. I knew I wanted to be a surgeon, and I did my rotation in neurology. In those days we didn’t have CT or MRI scans, and I loved the idea of finding out what the patient had by being a detective. The combination of liking neurology but having a surgeon mentality led me to neurosurgery.

How long did it take you to write your book?

Four years. I wrote it for two years with Jeanne Belisle Lombardo. I dictated every Thursday, and we started chronologically. Our agent said that was too boring for the reader, so we went back to the drawing board and put it together as it is now—where we start off with a case and hook the reader. We also put more dialogue in.

How were you able to remember the details of your life so well?

Once I started talking about a piece of history or a memory, it kind of flowed along. My wife always says I never forget anything; I have the memory of an elephant. Sometimes that’s good; sometimes that’s bad.

Why was it important to you to write and publish your story?

I gave a talk in 2004 as president of the American Academy of Neurological Surgery. The meeting in Dresden was in combination with the German Academy of Neurosurgery. My presidential speech was titled, ‘A Personal Reflection of the Cold War.’ Afterward, the German neurosurgeons were basically in tears saying, ‘I’m so glad you told this story. You’ve got to write this up.’ I didn’t think much of it then. I operated for six more years. As I told some stories of my patients and what people called my balanced life—that I could coach soccer for 15 years and still be a neurosurgeon—people kept saying, ‘You should write this up.’ So, that’s how it came about. I was encouraged to write my story.

What was the most challenging part of writing the book?

I’ve edited seven or eight textbooks in neurosurgery, and that was easy. The publisher came to me and said, ‘Can you edit this book on spinal neurosurgery?’ This was totally different because we had to find an agent and a publisher. So first of all, it was challenging to write the book and not make it sound like a sob story. Then once we got an agent, the agent said we needed a support website. Then the website needed pictures. My wife and I kept saying, ‘Well, let’s get it finished the way it should be.’

If you were to edit your book now, is there anything you’d change?

In retrospect, I thought I got a little bit too personal at times and maybe should not have. At the time it seemed natural, but then when I saw it in print—oh boy.

What was the most rewarding part about writing the book?

I think the most rewarding part was hearing relatives, friends, and even total strangers say that it’s an inspiring story. I kept hearing: you’re the American Dream. I guess I am—being an immigrant, working on a chicken farm for five years, working through college at Jack in the Box, and then getting into medical school.

Do you think you would still specialize in spine if you were entering neurosurgery today?

I probably would because spine surgery totally changed in the last 20 years. As I mentioned in the book, I took those cases because I needed to make money, and back then we put patients either on absolute bed rest or in a halo. We had no instrumentation of the spine. The combination of imaging, robotics, and minimally invasive surgery has totally changed the landscape of spine. It’s a very, very exciting subspecialty of neurosurgery now. We can treat many more things.

Do you think it’s as difficult to get established as a neurosurgeon today as it was when you were starting out?

Yeah, it’s pretty tough. It’s a long road to become a neurosurgeon. Four years of high school, four years of college, four years of medical school, and then seven years of neurosurgery residency. Then to get board certified, you need to take your oral boards within five years of finishing your residency. It’s a long haul, but it’s rewarding. Also, neurosurgery is not for the meek. It’s a combination of physical, mental, and psychological fortitude, as well as of course being hand-eye coordinated.

Do you credit your upbringing with helping you to persevere through the turf wars and pedicle screw controversy?

I think that certainly didn’t hurt. Going to high school, participating in sports, and then going home and cleaning chicken pens every day—that did take a lot of perseverance. Same with working 35 hours a week at Jack in the Box during college, playing soccer, and graduating summa cum laude.

You shared some difficult memories in your book, like the cases that didn’t have the outcomes you had hoped for. What was it like to relive those?

Well, the reason I did that is there are failures. The human body is not the same in everybody. Those complications and bad outcomes that I had, they lived with me. They still live with me. In neurosurgery, there are complex cases. There will be complications, even in the best of hands. I wanted to share that.

What are you most proud of in your career?

My children.

What do you think makes a good neurosurgeon?

The 4Hs: hard work, hope, honesty, and humility. Also, being compassionate to the patient and emphasizing that you are here to help.

What advice do you have for aspiring neurosurgeons?

You need to make sure that your family is happy. You also have to choose if you want to go the academic route or private practice, but either way, make sure your spouse is satisfied with the choices you make. Work hard, but don’t forget to have a balanced life. Neurosurgery demands a lot of time, but that doesn’t mean you can’t have an outside life as well.

Dr. Sonntag’s book is available at Amazon and Barnes and Noble. This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.