The Evolution of Spine Surgery: Ancient Egypt to the Present

The accident severed the ligaments connecting his skull to his spine – an injury formally known as occipitoatlantal dislocation but often referred to as internal decapitation. Timothy also had a blood clot the size of a golf ball pressing against his brainstem.

Doctors at Barrow discovered the blood clot, which was drained by Neurosurgeon Dr. Robert Spetzler, with an experimental magnetic resonance imaging machine which Barrow had agreed to test just three months earlier. Unlike most MRI magnets at the time, the new magnet would not interfere with Timothy’s life-support machines.

The metal rod that was successfully used to reattach the boy’s skull to his spine during the five-hour operation was designed and placed by Dr. Volker Sonntag. He still has the vise he used to bend the rod himself.

Doctors had only given Timothy a five percent chance of survival, but he eventually made a full recovery.

Improvements like these in imaging and spinal instrumentation have significantly contributed to the evolution of spine surgery over the past few decades, but mankind has been gathering knowledge of the spine and spinal cord for thousands of years.

Ancient Beginnings

“The history of the spine basically starts in Egypt,” said Dr. Mark Preul, director of neurosurgery research at Barrow. “The Egyptians were fairly aware of not exact diseases, but they were aware of the results that happened, especially after injuries. There were a lot of industrial sort of injuries at that time and also injuries from war.”

Physicians in ancient Egypt did not perform actual surgical procedures, but they made observations about how different sites of injury, such as different levels of spinal injuries, affected normal body functions.

“Because they were dealing with body preparation for death, the Egyptians had this kind of preoccupation with health and proper function of the body,” Dr. Preul said. “So, they made really good observations about how the body is actually not functioning correctly.”

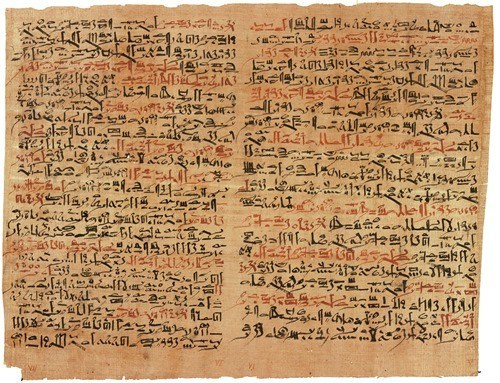

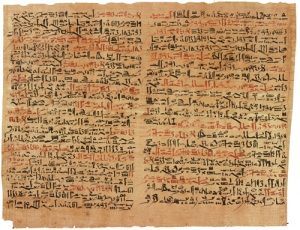

The first known written documentation of such observations was in the Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus dating back to the 17th century B.C. It described 48 cases of traumatic injuries, including six spinal injuries.

“It’s really the first time that documentation is made of the mechanisms of injury and the mechanisms of disease, and they’re observed and attributable to what the causes were,” Dr. Preul said. “It’s also important because the Edwin Smith Papyrus is really the first time we have, in written form, evidence of neurological observations.”

Knowledge of the spine and spinal cord continued to advance when the Greeks arrived in the city of Alexandria, which Alexander the Great established after conquering Egypt in 332 B.C.

Alexander the Great’s successor, the Ptolemaic dynasty, founded a library and museum that drew philosophers from around the world.

“The Ptolemys established an environment in Alexandria that was very open to learning, to discussion, and to new ideas,” Preul said. “Almost anything was open to discovery and investigation.”

One experiment conducted in Alexandria that was not permitted elsewhere in the Mediterranean was vivisection. Greek philosophers cut open the backs of living prisoners to study the spinal column.

The Birth of Spine Surgery

Knowledge of spinal anatomy and pathologies combined with better instrumentation and the use of ether and chloroform as anesthesia led to the start of surgical procedures in the mid-1800s.

“There was maybe some surgery being done around the early part of the 1800s or the late part of the 1700s, but that was mostly on soldiers in battle,” Dr. Preul said.

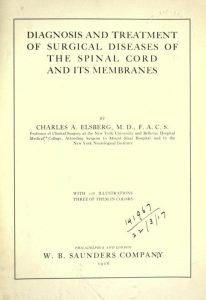

Surgery of the spine specifically began in the late 1800s, but it was not systematized until around 1916 when Dr. Charles Elsberg, a neurosurgeon from New York, published a textbook entitled “Diagnosis and Treatment of Surgical Diseases of the Spinal Cord and Its Membranes.”

Dr. Elsberg not only described his cases but instructed readers on how to perform surgical procedures on the spine and spinal cord for different conditions, presenting spinal disorders as a separate medical specialty.

“If you read this book, you would still know how to do spine surgery today,” Dr. Preul said. “It really set the tone for how to do spinal surgery and how people would write their books. When you’re picking out revolutionary books in medicine and surgery, this book is one of them.”

Surgeons who concentrated on the spine started to experiment with the implantation of certain materials, such as industrial cements that were created for aircrafts in the early 1900s, into the spine to fix deformities and defects.

During this time, spinal instrumentation came to be dominated by orthopedic surgeons. Neurosurgeons made few contributions to advancing treatment of spinal disorders in the 1960s and 1970s, performing decompressive laminectomies, in which they removed part of the vertebra to relieve pressure on the spinal cord caused by trauma or tumors. They called upon orthopedic surgeons for cases that required fusion.

Neurosurgeons as Spine Surgeons

“I began to do some cervical instrumentation, both anterior and posterior, and that was extremely radical,” said Dr. Volker Sonntag, who joined Barrow as a neurosurgeon in the early 1980s. “We started with cervical instrumentation because the cervical area was more of the domain of the neurosurgeon than the orthopedic surgeon.”

Dr. Sonntag’s expertise in spine surgery grew out of a need for cases. Before joining Barrow, he traveled between hospitals to operate, carrying his own neurosurgical instruments in his car. He sought out cases that did not interest his colleagues, such as cervical fractures and traumatic injuries.

Sonntag said he can recall performing many new spine procedures for the first time. He taught neurosurgeons how to braid wires for spine fixation and introduced a C1-2 interspinous wiring technique in 1989 that became known as “Sonntag C1-2 fusion.”

He traveled to Milwaukee in 1990 to learn thoracic-lumbar instrumentation from Dr. Sandy Larson, one of the few neurosurgeons who championed the neurosurgical treatment of complex spine cases in the 1970s and 1980s.

This desire to treat the spine trickled down to Barrow Neurosurgery Resident Dr. Curtis Dickman. Dr. Dickman ventured to Florida for a spine fellowship, where he learned pedicle screw fixation. Dickman, who retired in 2015, would later become an attending neurosurgeon at Barrow.

“We started doing thoracic-lumbar instrumentation, including pedicle screw fixation, and that raised a huge battle cry from the orthopedic community,”Dr. Sonntag said.

With the exception of pioneers like Dr. Sonntag, organized neurosurgery and academic neurosurgery remained complacent with respect to their role in spinal care until the Accredited Council of Graduate Medical Education began the process of approving spine fellowships in 1989. Neurosurgeons feared orthopedic surgeons would take over complete care of the spine.

Neurosurgeons formed a task force in 1991 to define the role of neurosurgeons in medical care of the spine and concluded that the entire spine should be an integral part of neurosurgical training. The committee created guidelines for training neurosurgery residents in spine care, which were later adopted by the American Association of Neurological Surgeons and the Congress of Neurological Surgeons.

Dr. Sonntag, who served as assistant chairman, and other members of the task force sent letters to program directors to encourage them to train their residents in spine surgery. The committee also pushed for more research on the spinal cord and column.

A turf battle ensued over the spine between the neurosurgical and orthopedic communities.

“It got to the point where even my own associates would stop me in the hall and say, ‘Why are you doing this? Let the orthopedic surgeons do the instrumentation and we’ll do the decompression. That’s what we’ve always done,’ ” Dr. Sonntag recalled. “But since organized neurosurgery decided that we should teach our residents instrumentation of the whole spine and we were one of the major teaching and training institutions of residents in the country, I continued on.”

When the medical executive committee of St. Joseph’s Hospital asked Sonntag to stop performing thoracic-lumbar instrumentation, Dr. Spetzler asked that Dr. Sonntag’s 12 cases be independently reviewed in a blind study along with 12 cases performed by orthopedic surgeons.

When the results came back in 1990, the committee granted Dr. Sonntag privileges to continue thoracic-lumbar instrumentation. This helped settle the controversy at Barrow, but disputes between neurosurgeons and orthopedic surgeons continued across the country.

The president of the American Association of Neurological Surgeons appointed Dr. Sonntag and other neurosurgeons to a liaison committee. In August 1993, neurosurgical and orthopedic representatives met in Chicago to discuss the future of spine surgery and began to form a more cordial relationship.

A Common Enemy: The Fight Over Pedicle Screws

A common enemy united neurosurgeons and orthopedic surgeons when a group of lawyers discovered that pedicle screws had not been approved by the Food and Drug Administration. The lawyers filed lawsuits against the manufacturers of the screws and the surgeons who used them, accusing the surgeons of malpractice.

Dr. Sonntag said he informed his patients that the screws were “off label,” and the FDA was developing a study to possibly reclassify pedicle screws. The study, performed in 1993 and completed in 1994, found that pedicle screws were as safe and effective as other internal fixation devices, but the FDA did not immediately reclassify the screws.

Newspaper advertisements solicited patients with pedicle screws in their backs, and ABC “20/20” aired a segment in December 1993 that was highly critical of the devices.

But after the FDA reclassified pedicle screws on July 27, 1998, most of the lawsuits were dropped.

Spinal instrumentation continued to improve, and the American Board of Neurological Surgery changed the definition of a neurosurgeon’s role to include treatment by fusion and instrumentation.

“Now, we have more sophisticated instrumentation, we have arthroplasty, we have robotics that we use to put in screws, we have minimally invasive spine surgery, and we understand biomechanics much better,” Dr. Sonntag said. “Spine has come a long way in neurosurgery.”

Related: The Evolution of Spine Surgery: Minimally Invasive Techniques and Artificial Discs