Gliomas

Overview of Gliomas

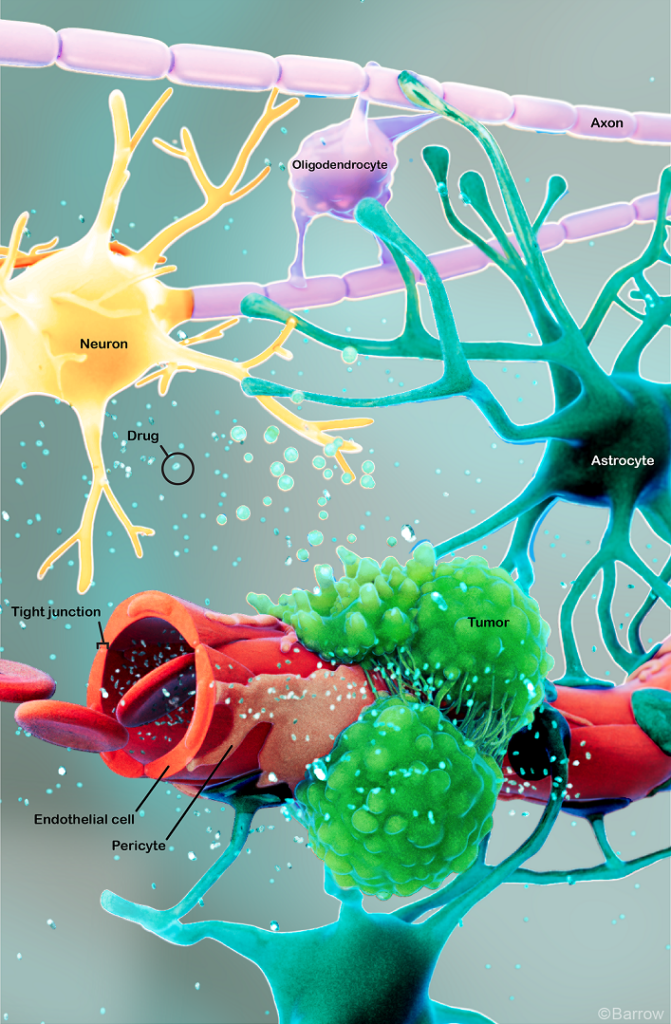

Gliomas are a type of tumor that originates in the glial cells of the brain or spinal cord. Glial cells support, nourish, and protect neurons, which are the primary cells in the nervous system.

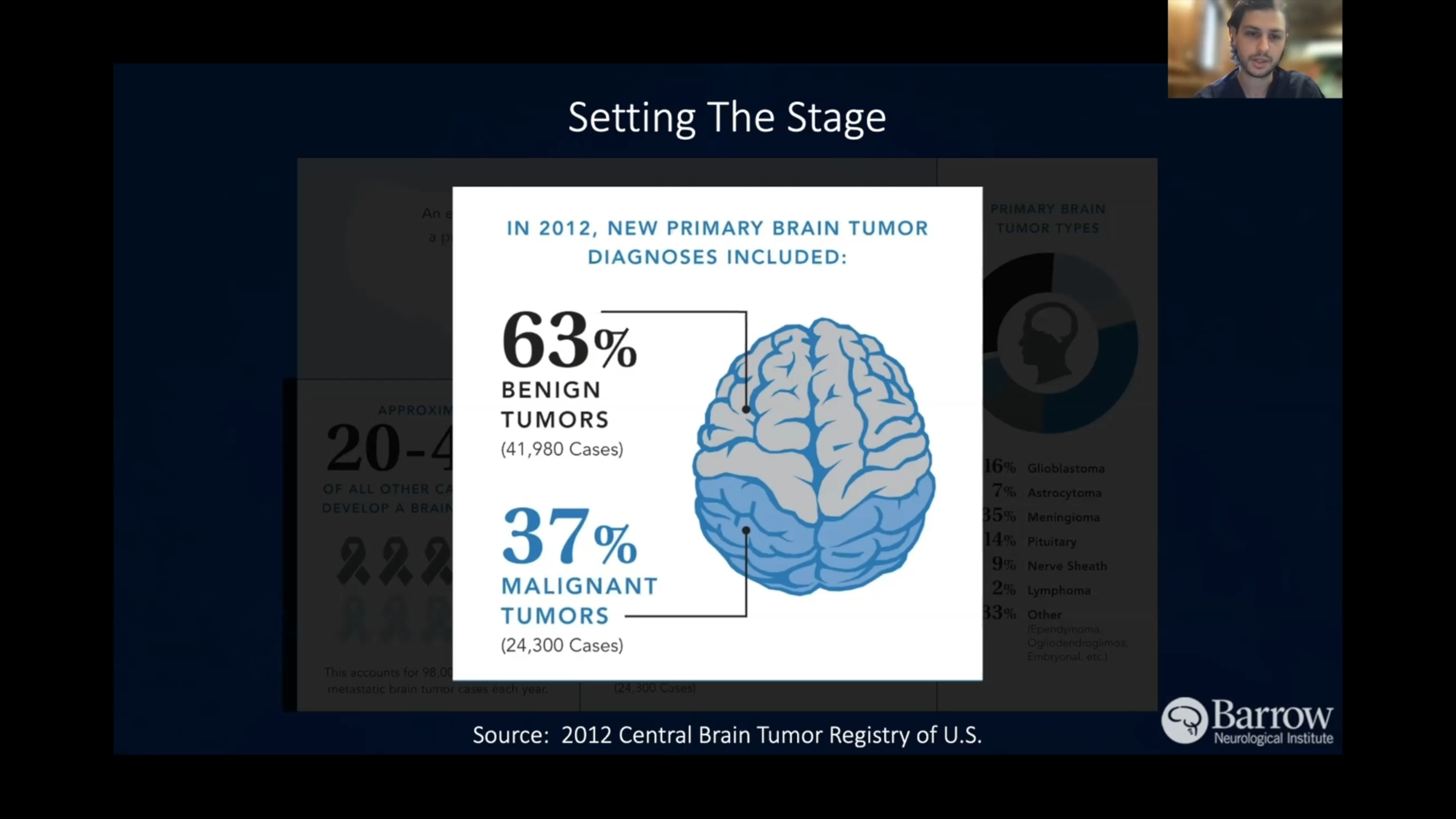

Gliomas are the most common type of primary brain tumor, meaning they start in the brain or spinal cord rather than spreading to the central nervous system (CNS) from another part of the body. Though most gliomas are malignant, they can be benign (low-grade, noncancerous) or malignant (high-grade, cancerous).

There are three main categories of gliomas based on the type of glial cell origin. They include:

- Astrocytomas: These tumors stem from astrocytes, star-shaped cells that provide nutrients and support to neurons. They usually arise in the cerebrum, or the outer part of the brain, but they also occur at the base of the brain in the cerebellum. The most aggressive form of an astrocyte is glioblastoma (GBM), a highly malignant astrocytoma. Astrocytoma is the most common glioma, while GBM is the most aggressive type.

- Oligodendrogliomas: These tumors originate from oligodendrocytes, or cells that produce the myelin sheath that insulates nerve fibers. Between 2 to 4 percent of primary brain tumors are oligodendrogliomas, and they’re most common in young and middle-aged adults.

- Ependymomas: These tumors develop from ependymal cells, which produce cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and line the brain’s ventricles and the central canal of the spinal cord. Ependymomas account for only 2 to 3 percent of primary brain tumors, making them quite rare. However, they make up 8 to 10 percent of children’s brain tumors, and they’re more likely to affect children under the age of ten.

Doctors also classify gliomas into four grades based on their behavior, aggressiveness, and how the tumor cells appear under a microscope. These grades include:

- Grade 1: These tumors are slow-growing and feature cells that look almost normal. Grade 1 gliomas are well defined, meaning the tumor has clear boundaries, making complete removal possible in most cases. While Grade 1 gliomas are noncancerous, they can still cause symptoms if they press on important brain or spinal cord structures. Pilocytic astrocytoma is a common Grade 1 glioma found in children.

- Grade 2: These tumors are also slow growing but appear more abnormal under a microscope than Grade 1 gliomas. Grade 2 gliomas can also infiltrate nearby brain tissue, making them harder to remove entirely with surgery, and they have a higher potential to become cancerous over time. A common Grade 2 glioma is oligodendroglioma, which can have a better outlook than other Grade 2 gliomas.

- Grade 3: These tumors grow more rapidly and tend to invade surrounding brain tissue, making them more challenging to remove with surgery. Grade 3 gliomas are malignant, making them more likely to recur after treatment. Two commonly seen forms of Grade 3 gliomas include anaplastic astrocytoma, a more aggressive form of astrocytoma, and anaplastic oligodendroglioma, a malignant tumor originating from oligodendrocytes.

- Grade 4: These are the most aggressive and fast-growing gliomas, with abnormal-looking cells that grow rapidly and often spread into other parts of the brain. Glioblastoma is the most common and deadliest form of glioma. Invasive and fast-growing, they’re quick to overwhelm the brain despite seldom spreading to other body parts.

What causes gliomas?

The exact cause of gliomas has yet to be fully understood. While most occur sporadically—without a clear genetic cause—certain genetic conditions can increase the risk. These include:

- Neurofibromatosis type I (NF1) and type II (NF2): Type I is associated with an increased risk of developing low-grade gliomas, while type II increases the risk of developing ependymomas and meningiomas.

- Li-Fraumeni syndrome: This genetic condition increases the risk of multiple cancers, including gliomas.

- Turcot syndrome: This rare genetic disorder causes small growths or polyps in the intestines that lead to colorectal cancer and increases the risk of brain or spinal cord tumors like glioma or pituitary adenoma.

Other factors that can increase the risk of developing a glioma include:

- Family history: Having a family history of brain tumors may slightly increase the risk of developing glioma, although familial cases are rare.

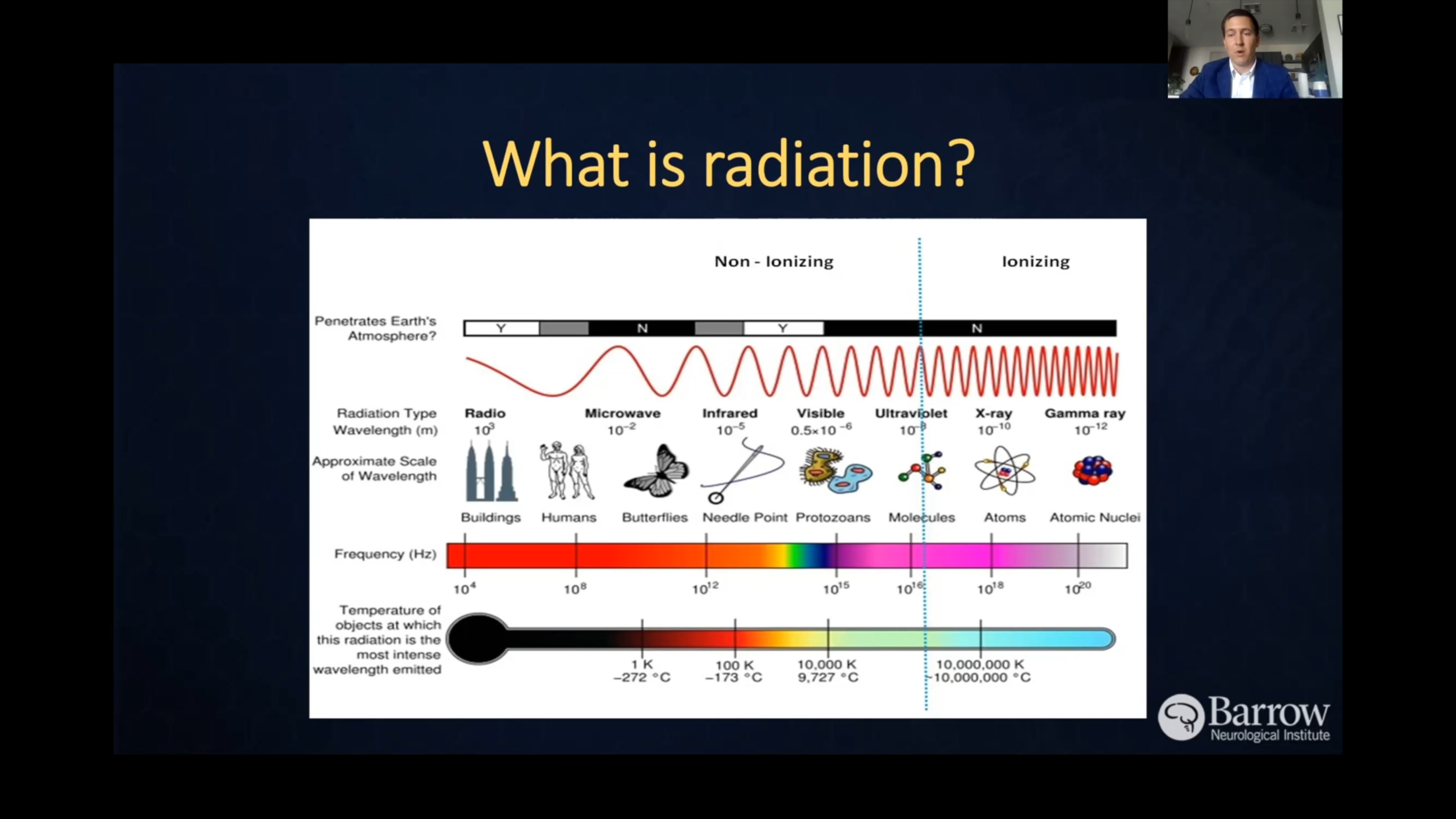

- Radiation exposure: Exposure to ionizing radiation, like radiation therapy for another cancer, increases the risk of developing gliomas. However, this only accounts for a small number of cases.

- Age: Gliomas are more common in adults, with the risk increasing with age. Glioblastomas, the most deadly form of gliomas, are most common in people over 50, but they can occur in people of all ages.

Glioma Symptoms

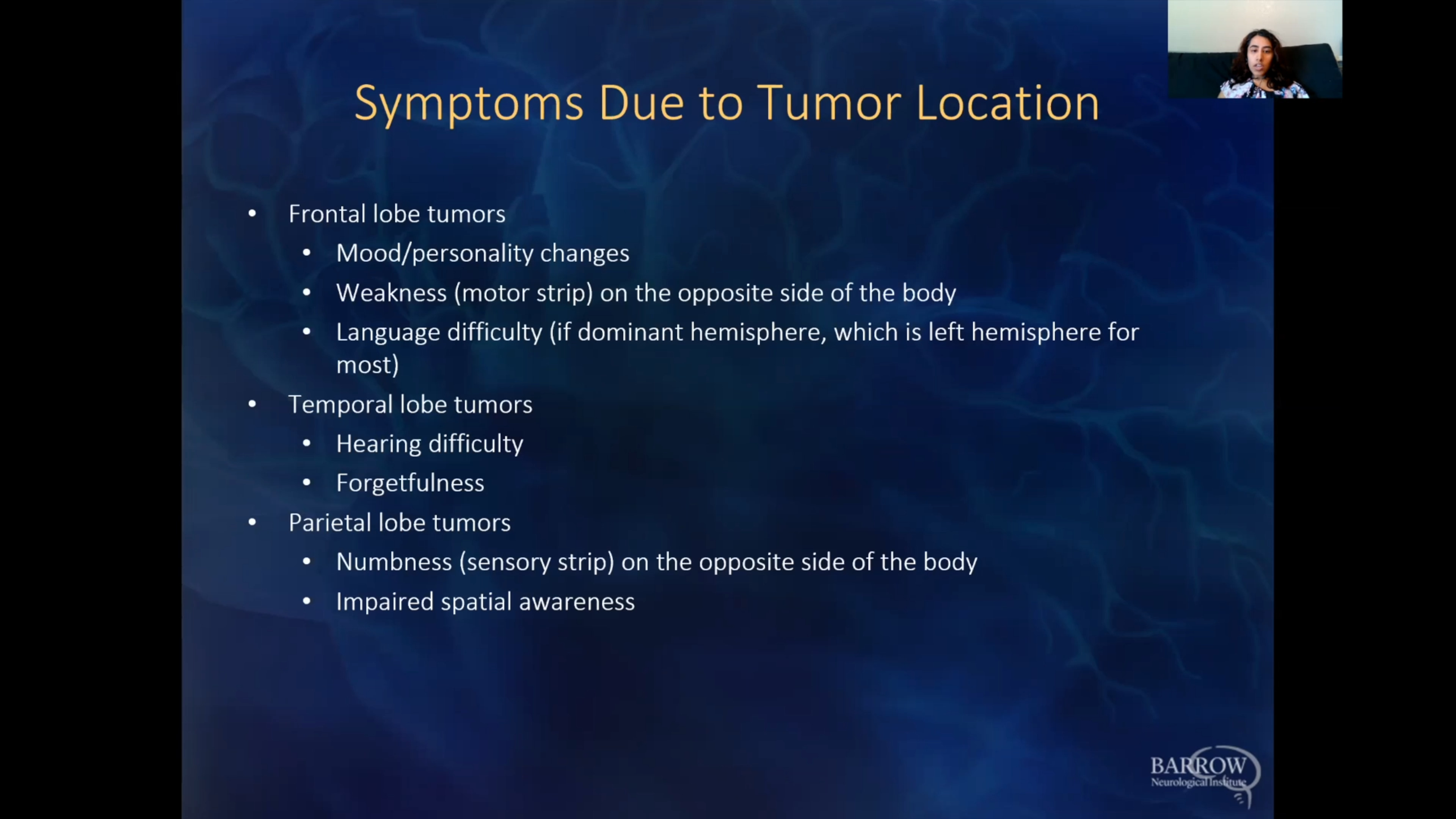

The symptoms of glioma vary, depending on its location, size, and growth rate. While they may initially be subtle, gliomas tend to produce multiple neurological symptoms due to their growth in the brain or spinal cord.

Symptoms you might notice if you or someone you know has a glioma can include:

- New onset or change in the pattern of headaches: These include headaches that aren’t improving with typical headache remedies, or you’re experiencing them more often, or they’re growing in intensity or worsening with activity.

- New onset of seizures: Often one of the first symptoms of gliomas,seizures occur because the glioma disrupts your brain’s regular electrical activity. Seizures can range from muscle jerks and spasms to a loss of consciousness and body functions. Changes in vision or smell can also indicate a seizure.

- Vision or speech problems: Tumors near the occipital lobe, which is responsible for vision, can cause visual disturbances. Tumors near the speech centers in the left frontal or temporal lobes can lead to difficulty speaking or understanding language.

- Sensory changes and weakness: Tumors can cause changes in sensation, like numbness, tingling, or loss of sensation in parts of your body, as well as feelings of weakness and a loss of coordination.

- Balance or coordination issues: Tumors in your cerebellum, which controls balance and coordination, can cause difficulty with fine motor skills.

- Unexplained nausea or vomiting: Increased pressure inside your skull from a glioma can result in nausea and vomiting.

- Fatigue or drowsiness: Gliomas can cause significant fatigue due to the tumor’s interference with your brain’s ability to function correctly.

- Personality or behavior changes: This can manifest as new or unusual emotional states, like changes in judgment, aggressiveness, or loss of initiative. Depression and anxiety can also be an early symptom of a tumor, specifically in the frontal lobe of the brain.

It’s important to note that these symptoms can overlap with those caused by other conditions. However, if you or someone you know is experiencing any of these symptoms—especially if they’re persistent or severe—it’s critical to consult a healthcare professional for evaluation. Early detection is essential for improving outcomes.

Glioma Diagnosis

A glioma diagnosis requires several steps to accurately diagnose your tumor’s type, location, and extent.

Doctors frequently use the following exams and imaging options in diagnosis:

- Physical and neurological exam: First, your healthcare provider will ask about your symptoms, overall health, and any risk factors you might have for a glioma, including family history. Next, they’ll complete a neurological examination to assess your neurological function, including reflexes, coordination, strength, and sensation.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): An MRI is the primary imaging test to detect and diagnose a glioma. This imaging study provides detailed images of your brain and helps identify the tumor’s location, size, and characteristics.

- Computed Tomography (CT): Although an MRI is often the first choice in neuroimaging, a CT scan can help evaluate tumor size and location by relying on X-rays to create detailed cross-sectional brain images.

- Biopsy: If your imaging results suggest a tumor, a definitive glioma diagnosis will require a biopsy. A biopsy establishes an exact diagnosis by removing a small tissue sample from the tumor surgically or through stereotactic biopsy. Neuropathologists then examine the tissue under a microscope to determine the type of cells present, whether they’re cancerous or noncancerous, and other essential characteristics that will guide your treatment decisions.

- Molecular testing: Genetic and molecular testing of gliomas can help identify specific mutations that influence your prognosis and treatment.

Additional tests may be run to assess the extent of the tumor and its effects on brain function. These can include positron emission tomography (PET) scans, which evaluate the metabolic activity of brain tumors and determine their aggressiveness, and electroencephalography (EEG), which assesses the brain’s electrical activity.

Glioma Treatment

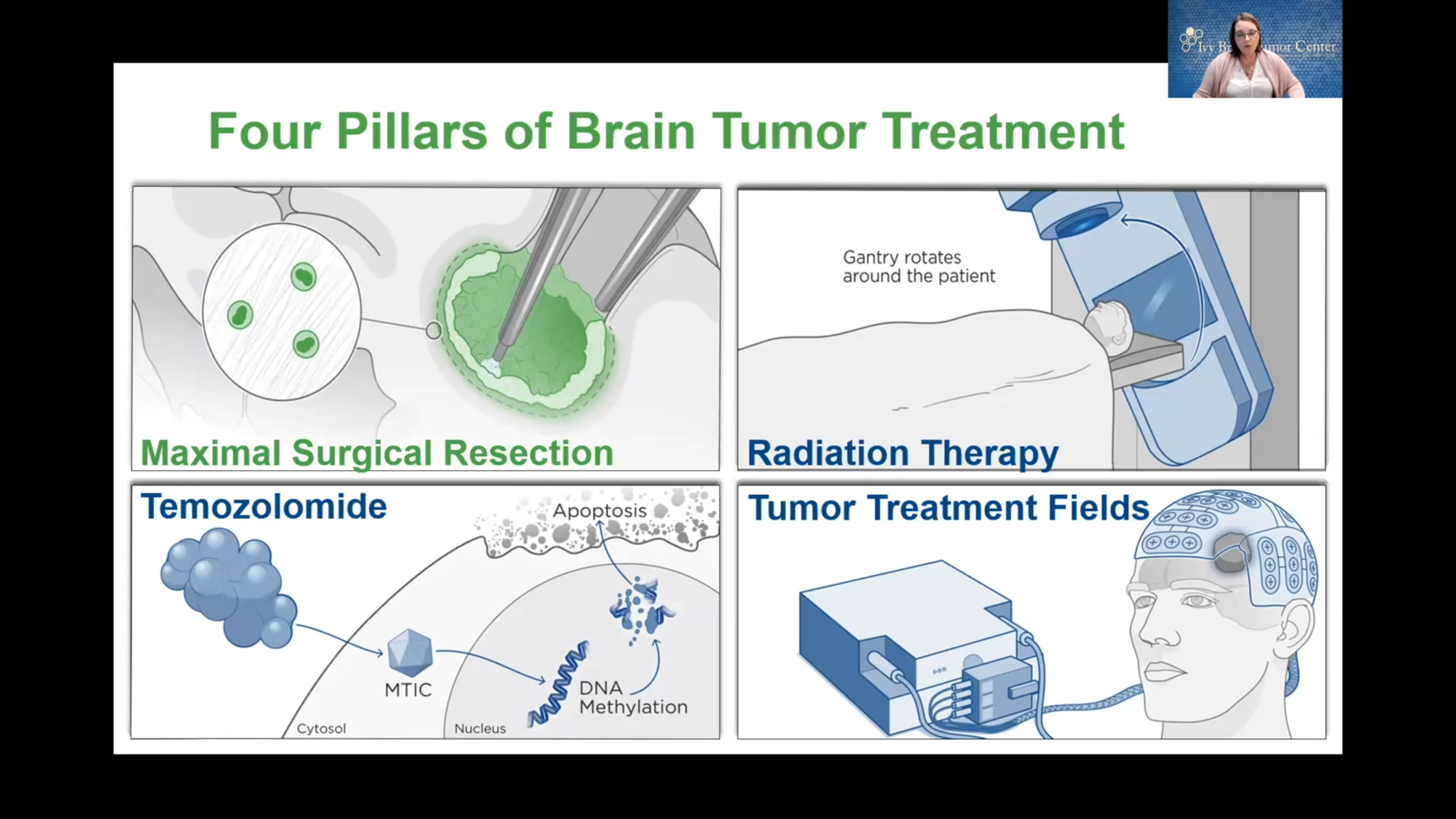

As with all other facets of a brain or spine tumor, optimal treatment will depend on the tumor’s type, location, size, growth rate, and your overall health. Generally speaking, treatment for a glioma will involve surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy, with targeted therapies and clinical trials as an option for sourcing more treatments.

Neurosurgical Treatment

Neurosurgical resection is often the first step in treating gliomas, particularly if your neurosurgeon can safely reach the tumor. The goal of surgery is to remove as much of the tumor as possible—known as a maximal resection—while minimizing damage to surrounding healthy brain tissue.

The application of neurosurgery to treat tumors of the brain and spinal cord is called neurosurgical oncology. Some of the most common procedures used to treat gliomas include:

- Craniotomy: Craniotomy is the most common neurosurgical procedure for gliomas. During a craniotomy, a neurosurgeon makes an incision in the scalp, removes a portion of the skull, and accesses the brain to remove the tumor with intraoperative imaging and highly specialized tools. The goal of a craniotomy is to remove the bulk of the tumor, except in cases where the glioma occupies a highly sensitive area of the brain.

- Awake craniotomy: Awake brain surgery, or awake craniotomy, is a specialized surgery for brain tumors in areas that control critical functions, like speech or movement. During awake brain surgery, the patient is awake and alert while the surgeon removes the tumor, allowing the surgical team to monitor brain function in real time and avoid damaging critical anatomy.

- Minimally invasive techniques: In some cases, minimally invasive surgical techniques can be used to remove brain tumors. These techniques involve smaller incisions and specialized instruments to access and remove the tumor, like endoscopic surgery and laser interstitial thermal therapy (LITT). These techniques can offer shorter recovery times, reduced risk of complications, and more minor scars.

If your neurosurgeon can’t remove the entire glioma, the result is called a subtotal resection. A subtotal resection may be necessary if the glioma cannot easily be separated from healthy brain tissue or is located in a highly sensitive region.

Nonsurgical Treatments

After surgery, high-grade gliomas often require nonsurgical treatments to target the remaining tumor cells and reduce the risk of recurrence. These treatments can include:

- Radiation therapy: Radiation therapy uses precisely aimed beams of radiation to destroy tumors in the body. While it doesn’t remove the tumor, radiation therapy damages the DNA of the tumor cells, which then lose their ability to reproduce and eventually die. Radiation therapy is often used after surgery—particularly for high-grade gliomas—to reduce the risk of recurrence.

- Stereotactic radiosurgery: This treatment method uses an exact form of radiation that delivers a focused dose to the tumor while sparing surrounding healthy tissue. The two most common forms are:

- Gamma Knife radiosurgery: This option destroys abnormal tissue through radiation beams focused on a precise tissue area and is only lethal to cells within the immediate vicinity. The Gamma Knife can only be used to treat lesions in the head, as it involves attaching a metal frame to the skull for target accuracy.

- CyberKnife radiosurgery: This technique uses targeted energy beams to destroy tumor tissue while sparing healthy tissue. It uses image-guided robotics to deliver surgically precise radiation to help destroy tumors.

- Chemotherapy: Chemotherapy relies on drugs given orally or intravenously to kill or stop the growth of cancer cells. It’s often combined with radiation therapy to treat gliomas, especially in the case of glioblastoma.

- Temozolomide (TMZ): Temozolomide is a commonly used chemotherapy drug for gliomas. It is usually taken during and after radiation therapy.

- PCV regimen: For low- to intermediate-grade gliomas, such as oligodendrogliomas, a combination of three chemotherapy drugs—procarbazine, lomustine (CCNU), and vincristine—is often used.

- Intrathecal chemotherapy: In some cases, chemotherapy can be delivered directly into the cerebrospinal fluid, especially for tumors that have spread to the spinal cord.

- Targeted therapy: A newer area of treatment, targeted therapy uses compounds to reach specific molecules vital to cancer cell reproduction. By effectively targeting and interfering with these molecules, cancer growth is slowed.

- Tumor-treating fields (TTF) therapy: TTF therapy is used to treat aggressive gliomas, especially glioblastoma, and neuro-oncologists often prescribe it in conjunction with chemotherapy. During this treatment, sticky pads are attached to the scalp, and wires connect the pads to a portable device. This device generates an electrical field that damages the glioma cells.

- Immunotherapy: This newer treatment involves a series of drugs that boost the body’s immune system to recognize and attack cancer cells. Immunotherapy for gliomas is still under research, although some strategies show promise.

- Corticosteroids: This class of medication can be used in the short term to reduce inflammation and brain swelling caused by glioma.

- Anticonvulsants: If a glioma has caused seizures, anti-seizure medications are prescribed as supportive care.

One Central Location with Multiple Treatment Options

At Barrow Neurological Institute’s world-class Brain and Spine Tumor Program, we treat people with complex tumors like gliomas in one robust, full-service location. Our sophisticated multidisciplinary team—neurosurgeons, head and neck surgeons, neuro-oncologists, medical oncologists, and radiation oncologists, to name a few—can offer you the latest treatments for head and neck cancers, including metastatic cancers.

We also give our patients access to various neuro-rehabilitation specialists to enhance their physical abilities, maximize independence, and support their mental health. Since gliomas—particularly high-grade ones—can significantly impact quality of life, supportive care is crucial.

Neuro-rehabilitation can include physical therapy to help you regain strength and balance, speech therapy to support speaking and expressing thoughts, and occupational therapy to aid in managing daily activities like bathing, dressing, and using the bathroom. Treating a brain or spinal cord tumor is about more than extending your life—it’s also focused on enhancing your quality of life.

Clinical Trials

In partnership with the Ivy Brain Tumor Center, Barrow Neurological Institute is proud to be one of the country’s largest sites for neurological clinical trials.

Clinical trials are part of the cancer research process to determine if new treatments are safe, effective, or even better than the current standard treatment. Although not yet FDA-approved, clinical trials can be the best option for those with difficult-to-treat tumors to improve the odds of finding an effective treatment for them and for future patients. If you’re diagnosed with a glioma, especially one with an aggressive grade like glioblastoma, you may be a candidate. To search for clinical trials that are now enrolling, visit here.

Common Questions

How common are gliomas?

Gliomas are the most common type of brain tumor in adults, making up 25 to 30 percent of all brain and central nervous system (CNS) tumors. What’s more, gliomas account for a large percentage of all malignant brain tumors. In the U.S. alone, glioblastoma is the most common malignant brain tumor.

Gliomas can occur at any age but are most commonly diagnosed in adults aged 45 to 65. However, certain gliomas, like pilocytic astrocytomas, are more common in children.

Who gets gliomas?

Gliomas are more common in adults than children, although they can happen in any age group. Glioblastoma, the most aggressive type, is typically seen in older adults, particularly those over 50. Men are slightly more likely to develop gliomas than women.

Gliomas are the most common type of brain tumor in children, accounting for around 50 percent of childhood brain tumors.

What is the prognosis for those with glioma?

The prognosis for a glioma depends on your overall health and the type, grade, and location of your tumor.

Low-grade gliomas (Grades 1 and 2) generally have a better prognosis because they grow slowly and are less aggressive. High-grade gliomas (Grades 3 and 4) are more aggressive and can develop rapidly, so they have a poorer prognosis—particularly glioblastoma, a Grade 4 glioma.

The extent of tumor removal plays a key role in prognosis. Complete resection, or removing as much tumor as possible, improves outcomes. Incomplete resection or tumors in areas where surgery is limited—for example, near critical brain structures—can lead to less favorable outcomes.

Younger patients generally have a better prognosis than older patients due to their better tolerance of aggressive treatments.

While gliomas, especially high-grade ones, can have a poor prognosis, the following steps can help improve outcomes after you or your loved one is diagnosed:

- Early detection: Diagnosing low-grade gliomas before they progress can lead to better treatment outcomes.

- Aggressive treatment: Complete surgical removal, followed by radiation and chemotherapy, can improve survival, especially in higher-grade gliomas.

- Clinical trial participation: Clinical trials can offer patients with aggressive or recurrent gliomas access to new therapies, such as immunotherapy, targeted therapies, or novel chemotherapeutic agents.

Can gliomas be prevented?

Currently, there is no known way to prevent gliomas. A large percentage of them happen without any identifiable risk factors.

The only known modifiable risk factor is radiation exposure, but avoiding necessary treatment isn’t feasible if you’re being treated for another type of cancer. While there is no specific lifestyle change that can prevent a glioma from developing, maintaining a healthy lifestyle—a balanced diet, regular exercise, and avoiding known risk factors like smoking—can reduce the risk of many types of cancer.

Additional Resources

References

- Chang EK, Smith-Cohn MA, Tamrazi B, Ji J, Krieger M, Holdhoff M, Eberhart CG, Margol AS, Cotter JA. IDH-mutant brainstem gliomas in adolescent and young adult patients: Report of three cases and review of the literature. Brain Pathol. 2021 Jul;31(4):e12959. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12959. Epub 2021 May 7. PMID: 33960568; PMCID: PMC8412065.

- Smith-Cohn MA, Celiku O, Gilbert MR. Molecularly Targeted Clinical Trials. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2021 Apr;32(2):191-210. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2020.12.002. Epub 2021 Feb 18. PMID: 33781502.

- Smith-Cohn M, Davidson C, Colman H, Cohen AL. Challenges of targeting BRAF V600E mutations in adult primary brain tumor patients: a report of two cases. CNS Oncol. 2019 Dec 1;8(4):CNS48. doi: 10.2217/cns-2019-0018. Epub 2019 Dec 10. PMID: 31818130; PMCID: PMC6912849.

- Chen R, Smith-Cohn M, Cohen AL, Colman H. Glioma Subclassifications and Their Clinical Significance. Neurotherapeutics. 2017 Apr;14(2):284-297. doi: 10.1007/s13311-017-0519-x. PMID: 28281173; PMCID: PMC5398991.