Oligodendroglioma

Overview

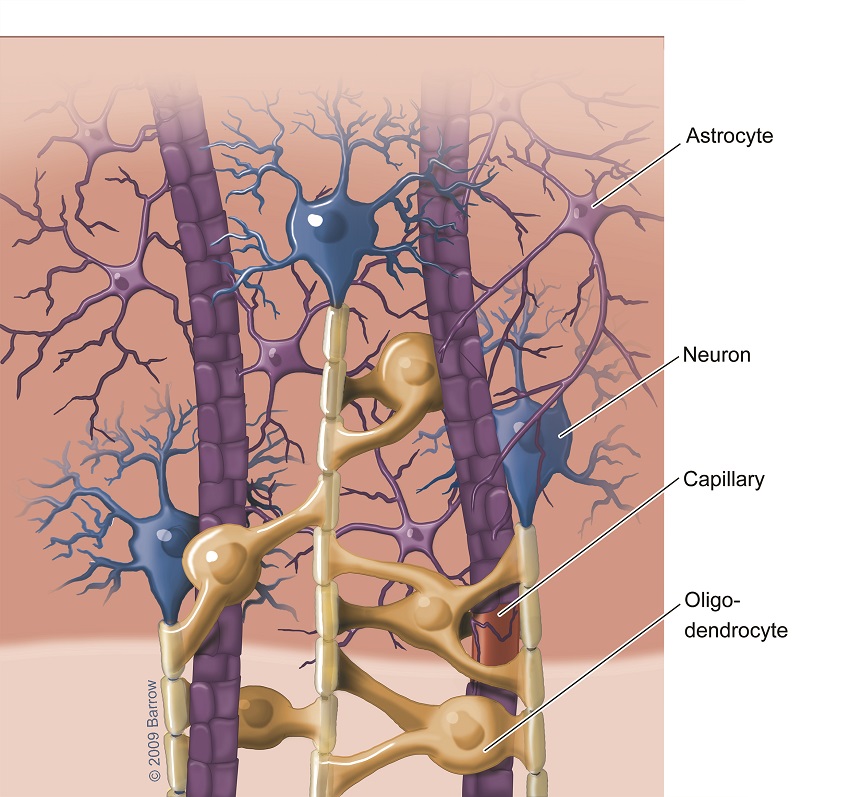

An oligodendroglioma is a type of brain tumor that grows from a special kind of cell in the brain called an oligodendrocyte. Oligodendrocytes help support and protect neurons, or nerve cells, by creating a layer of insulation called myelin. Without myelin, neurons cannot send and receive signals throughout the network of neurons in the central nervous system.

Oligodendrogliomas are a type of glioma and tend to grow slowly, often over many years. Although they’re most common in adults, they can occur at any age.

Unlike other, more aggressive types of brain tumors, oligodendrogliomas are generally more mild in behavior. However, they still require medical attention and treatment because they can affect nearby brain tissue over time.

Doctors group oligodendrogliomas into two grades based on their characteristics and behavior. They include:

- Grade 2: Known as low-grade oligodendroglioma, these tumors grow slowly and can take years to cause noticeable symptoms. Under a microscope, these tumor cells look more like normal brain cells and show fewer irregular features. With treatment, patients with low-grade oligodendrogliomas have a strong prognosis, with many living for 10 years or more after diagnosis. Long-term remissions after treatment are common.

- Grade 3: Known as anaplastic oligodendrogliomas, these are higher-grade tumors that can grow rapidly, produce symptoms sooner, and have a higher tendency to spread within the brain. These tumor cells have a more irregular appearance, and they divide rapidly. A Grade 3 oligodendroglioma generally has a less favorable prognosis than a Grade 2 tumor. However, the quality of life after diagnosis will depend on a person’s treatment response, overall health, and age.

What causes oligodendroglioma?

Like many other types of tumors, the exact cause of oligodendrogliomas is unknown. Most appear to develop sporadically, meaning they happen by chance, without an inherited or environmental cause.

That said, there is a combination of genetic changes and, in some cases, environmental factors that can play a role in their development. They include:

- Genetic mutations: Many oligodendrogliomas have mutations in the IDH1 or IDH2 gene. Another hallmark is a genetic change called the 1p/19q codeletion, where certain sections of chromosomes 1 and 19 are missing. Lastly, mutations in the TERT promoter, which affects enzymes that help maintain the ends of chromosomes, are also common. Most of these genetic mutations are believed to arise spontaneously in cells rather than being inherited.

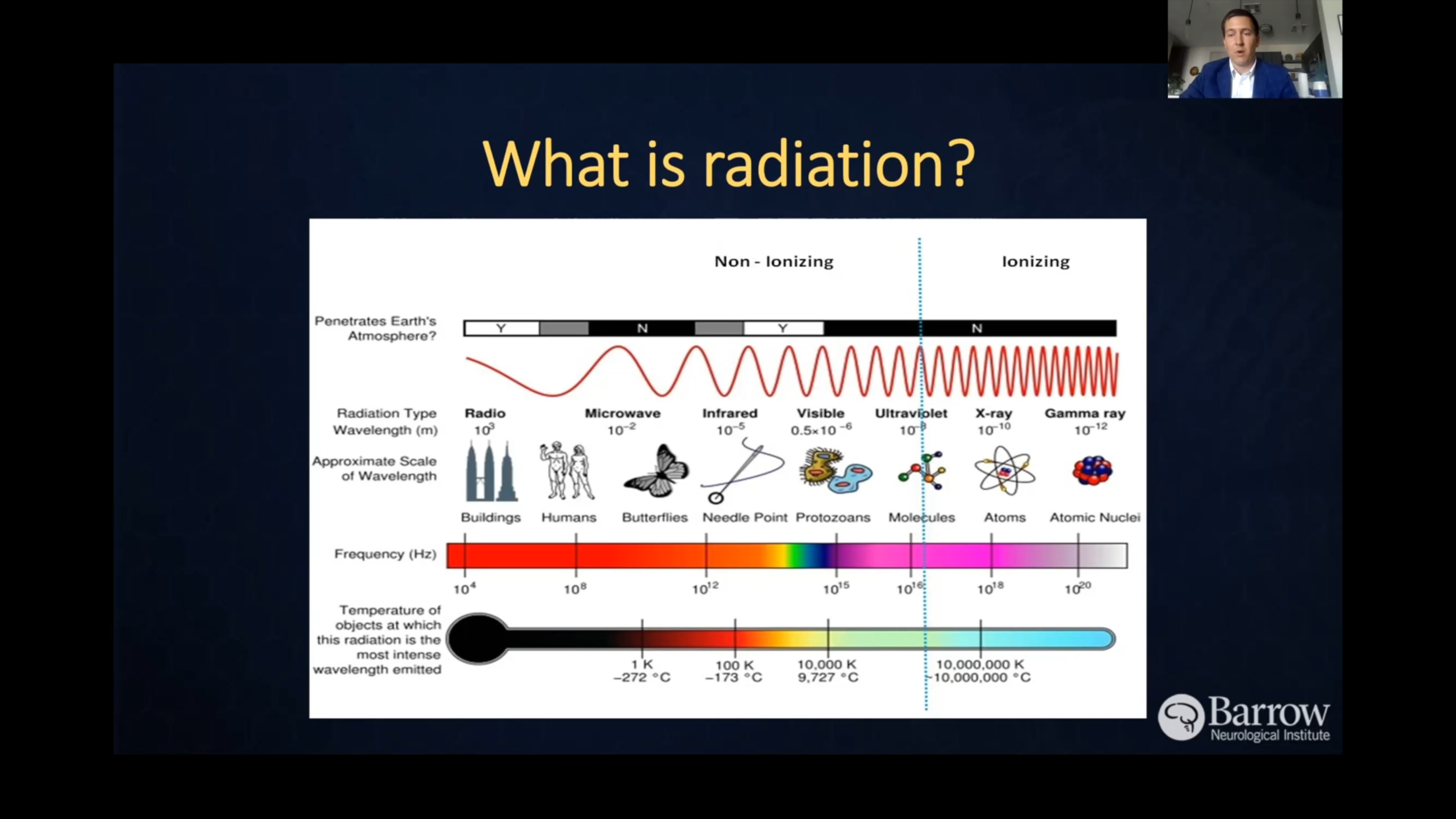

- Environmental factors: Although rare, high-dose ionizing radiation—for example, from radiation therapy for another cancer—has been linked to an increased risk of brain tumors, but this typically occurs only in those who have received radiation to the head. Currently, there’s no strong evidence linking lifestyle factors, like diet or smoking, to an increased risk of oligodendrogliomas.

- Genetic syndromes: Although most cases of oligodendroglioma are not inherited, a few exceptional genetic syndromes, such as Li-Fraumeni Syndrome, Turcot Syndrome, and neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), can increase the risk of gliomas in general, which includes oligodendrogliomas.

Oligodendroglioma Symptoms

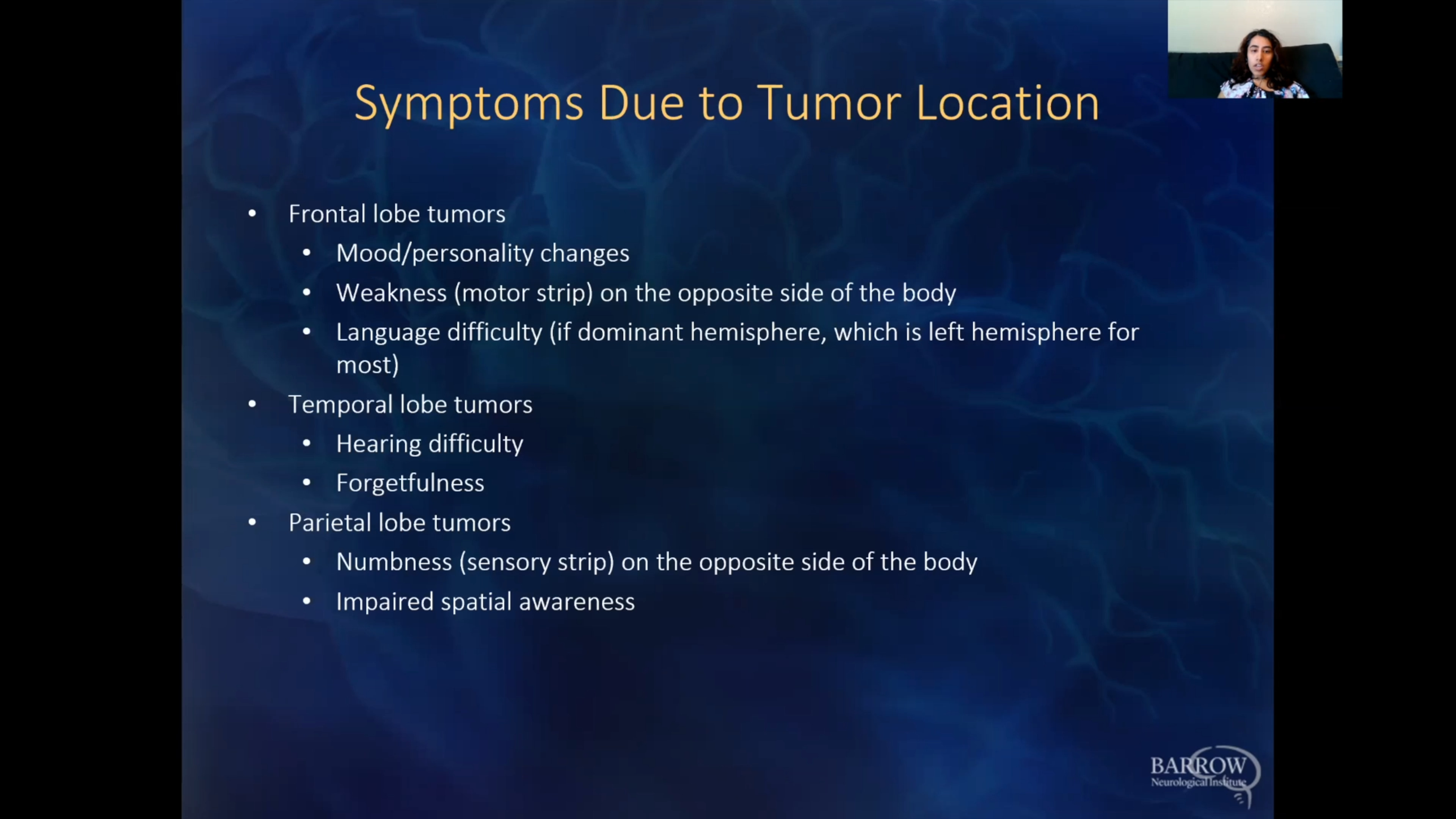

The specific symptoms of an oligodendroglioma depend on the tumor’s location, size, and the extent to which it presses on nearby brain tissue.

You or someone you know might experience the following symptoms if you have an oligodendroglioma:

- Seizures: The most common symptom of an oligodendroglioma is a seizure, which is disorganized electrical activity in the brain. Nearly 60 percent of people experience a seizure before being diagnosed. What a seizure looks or feels like can vary depending on the part of the brain affected, from mild symptoms, like small muscle twitches or stiffening, to more severe ones, such as body convulsions or a loss of consciousness.

- Headaches: Headaches that are persistent, don’t respond to typical prevention measures, and are worse in the morning can occur as the oligodendroglioma grows and increases pressure inside your skull.

- Behavioral changes: Confusion, difficulty focusing, and memory issues may arise, mainly if your oligodendroglioma grows in the frontal lobe. Personality changes or mood swings may also occur as the brain regions responsible for emotion and behavior are affected.

- Weakness or numbness: Weakness, numbness, or tingling sensations on one side of the body can occur, primarily if the tumor affects your motor cortex or another region of the brain responsible for movement.

- Speech or language difficulties: An oligodendroglioma in or near the temporal or parietal lobes may cause problems with speaking or understanding language, or symptoms like slurred speech or trouble finding the right words.

- Vision or other sensory changes: If your tumor affects the occipital lobe or visual pathways, you may experience blurred vision, double vision, or partial vision loss. Other sensory changes, like changes in taste or smell, may also occur.

- Balance and coordination problems: Tumors in or near the cerebellum or brainstem can cause issues with balance and coordination. You may even notice you feel clumsier than usual or have trouble with fine motor skills.

- Fatigue: Persistent tiredness and low energy can be a direct symptom of an oligodendroglioma or a side effect of the body’s response.

Because oligodendrogliomas are often slow-growing, symptoms usually appear gradually. Moreover, the same gradual symptoms, like reoccurring headaches or subtle cognitive changes, can be mistaken for less serious issues. This is why it is important to consult a trusted healthcare professional for evaluation and brain imaging studies to make a definitive diagnosis.

Oligodendroglioma Diagnosis

Oligodendroglioma diagnosis often requires a combination of tests, imaging studies, biopsy, and occasionally more invasive procedures to be as accurate as possible. Usually, doctors seek to identify two specific genetic mutations in an oligodendroglioma diagnosis: the 1p/19q codeletion, a particular change in the tumor cells’ chromosomes, and an IDH mutation.

The most common diagnostic tests for oligodendroglioma include:

- Physical and neurological exam: First, your provider will review your symptoms, medical history, and any risk factors you may have. Symptoms like headaches, seizures, or neurological deficits may prompt a further investigation. Next, a neurological examination will check your coordination, reflexes, strength, and other sensory functions.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): The most common test for diagnosing brain tumors, an MRI uses strong magnets and radio waves to provide detailed brain images to determine a tumor’s location, size, and characteristics. In imaging studies, oligodendrogliomas often show a “fried egg” appearance and may have areas of calcification.

- Computed Tomography (CT): CT scans rely on X-rays to create detailed cross-sectional images of the brain, helping to detect tumors, their sizes, and locations. While MRI is generally preferred, a CT scan can also help detect common oligodendroglioma calcifications or bone involvement in the spinal cord area.

- Biopsy: A biopsy is recommended to confirm an oligodendroglioma. During a biopsy, a small tumor sample is removed and sent to a pathology laboratory for analysis. There, pathologists examine the tissue under a microscope to determine the type of cells present, as well as other important characteristics that guide treatment decisions. For tumors in the brain, a biopsy is typically done surgically or through stereotactic biopsy.

- Genetic and molecular testing: Genetic testing for 1p/19q codeletion and IDH mutation is critical in distinguishing oligodendrogliomas from other gliomas and helping to guide the best treatments. The 1p/19q codeletion marker, present in all oligodendrogliomas, often means the tumor will respond better to certain types of chemotherapy and radiation.

- Lumbar puncture: If there’s a concern that the tumor has spread to the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), your doctor may suggest a lumbar puncture or spinal tap. However, this is an uncommon diagnostic tool for oligodendrogliomas, as they rarely spread beyond the brain.

Additional genetic and molecular tests, such as TERT promoter mutation and MGMT promoter methylation tests, may be done to confirm the extent of your oligodendroglioma and help further guide your diagnosis and treatment options.

Oligodendroglioma Treatment

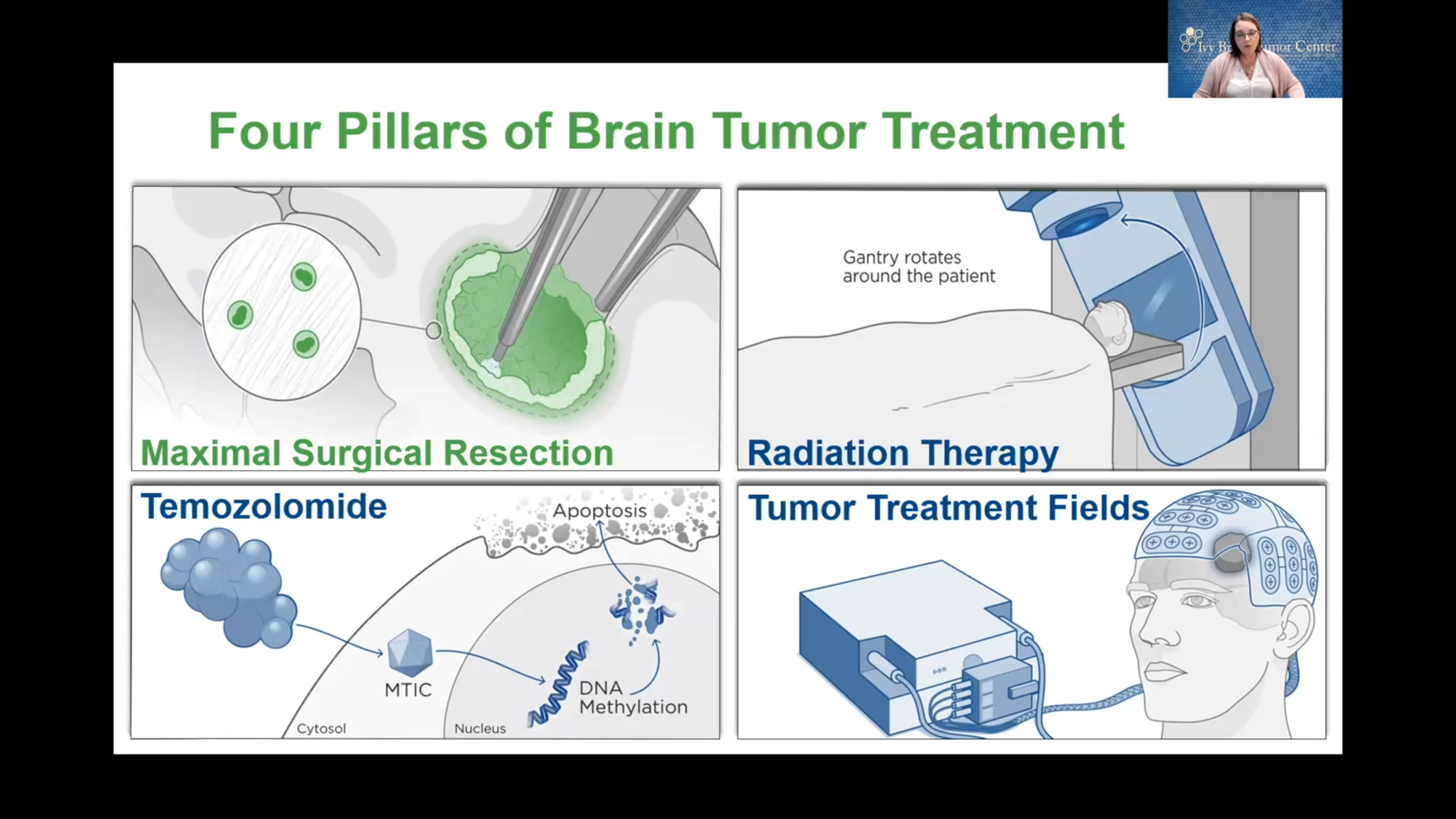

Neurosurgical resection is often the first step in treating gliomas, particularly if your neurosurgeon can safely reach the tumor. The goal of surgery is to remove as much of the tumor as possible—known as a maximal resection—while minimizing damage to surrounding healthy brain tissue.

Surgical Treatments

Surgery to remove as much of the tumor as is safely possible is generally the first step in treatment. This, in turn, will reduce your symptoms while supporting long-term control of the tumor, especially when combined with other treatments or therapies.

- Craniotomy: Craniotomy is the primary surgery for an oligodendroglioma. During a craniotomy, a neurosurgeon makes an incision in the scalp, removes a portion of the skull, and accesses the brain to remove the tumor with intraoperative imaging and specialized tools. The goal of a craniotomy is a maximal resection, or removing as much of the tumor as possible without damaging essential brain functions.

- Awake craniotomy: Awake brain surgery, or awake craniotomy, is a specialized surgery for brain tumors in areas that control critical functions, like speech or movement. During this procedure, the patient is awake and alert while the surgeon removes the tumor, allowing the surgical team to monitor brain function in real time and avoid damaging critical anatomy. Awake craniotomies are particularly valuable for tumors in the frontal and temporal lobes, where language and motor functions are located.

- Minimally invasive techniques: In some cases, minimally invasive surgical techniques can remove smaller or harder-to-reach tumors. These techniques involve smaller incisions and specialized instruments to access and remove the tumor, like endoscopic surgery and laser interstitial thermal therapy (LITT). These techniques can offer shorter recovery times, reduced risk of complications, and more minor scars.

Even with maximal resection, oligodendroglioma cells may remain, so neuro-oncologists often recommend follow-up treatments like radiation or chemotherapy. Regular imaging is also vital to check for recurrence.

Nonsurgical Treatments

Following surgery, oligodendrogliomas often require nonsurgical treatments to target the remaining tumor cells and reduce the risk of recurrence. And for those with favorable genetic markers, nonsurgical treatments can effectively manage oligodendrogliomas.

These treatments can include:

- Radiation therapy: Radiation therapy uses precisely aimed beams of radiation to destroy tumors in the body. While it doesn’t remove the tumor, radiation therapy damages the DNA of the tumor cells, which then lose their ability to reproduce and eventually die. Radiation therapy is often used after surgery—particularly for Grade 3 oligodendrogliomas—to reduce the risk of recurrence.

- Stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS): This nonsurgical treatment delivers a focused radiation dose to the tumor while sparing surrounding healthy tissue. SRS is not commonly used for oligodendrogliomas.

- Chemotherapy: Chemotherapy relies on drugs given orally or intravenously to kill or stop the growth of cancer cells. It’s often used after surgery, in Grade 3 oligodendrogliomas, or reoccurring Grade 2 oligodendrogliomas. Standard chemotherapy regimens include:

- Temozolomide (TMZ): An oral chemotherapy drug often used for oligodendrogliomas, temozolomide has shown effectiveness in improving outcomes—particularly in tumors with the 1p/19q codeletion.

- PCV regimen: For low- to intermediate-grade oligodendrogliomas, a combination of three chemotherapy drugs—procarbazine, lomustine (CCNU), and vincristine—is often used. This regimen has been especially effective in oligodendrogliomas with the 1p/19q codeletion and is frequently used alongside radiation therapy.

- Targeted therapies: A newer area of treatment, targeted therapies attempt to inhibit specific molecular pathways or mutations in tumor cells, aiming to halt tumor growth. Some examples include:

- Anti-angiogenic therapy: Drugs inhibiting blood vessel growth in tumors, such as bevacizumab, can help control swelling from brain tumors or radiation-related inflammation.

- IDH inhibitors: IDH inhibitors such as vorasidenib are used to treat low-grade IDH mutant glioma.

- Pain management: To help improve daily function, medications for pain, anti-nausea, and other supportive therapies may be prescribed.

- Anticonvulsants: If an oligodendroglioma has caused seizures, anti-seizure medications can be prescribed as supportive care.

- Corticosteroids: This class of medication can be used in the short term to help manage swelling around the tumor and relieve symptoms like headaches and nausea.

One Central Location with Multiple Treatment Options

At Barrow Neurological Institute’s world-class Brain and Spine Tumor Program, we treat people with complex tumors like oligodendrogliomas in one robust, full-service location. Our sophisticated multidisciplinary team—neurosurgeons, head and neck surgeons, neuro-oncologists, medical oncologists, and radiation oncologists, to name a few—can offer you the latest treatments for head and neck cancers, including metastatic cancers.

We also give our patients access to various neuro-rehabilitation specialists to maximize independence. Neuro-rehabilitation can include physical therapy to help you regain strength and balance, speech therapy to support speaking, expressing thoughts, or swallowing, and occupational therapy to aid you in managing daily activities like bathing, dressing, and using the bathroom. Treating a brain or spinal cord tumor is about more than extending your life—it’s also focused on enhancing your quality of life.

Clinical Trials

In partnership with the Ivy Brain Tumor Center, Barrow Neurological Institute is proud to be one of the country’s largest sites for brain tumor clinical trials.

Clinical trials are part of the cancer research process to determine if new treatments are safe, effective, or even better than the current standard treatment. Although not yet FDA-approved, clinical trials can be the best option for those with difficult-to-treat tumors to improve the odds of finding an effective treatment for them and for future patients.

To search for clinical trials that are now enrolling, visit here.

Common Questions

How common are oligodendrogliomas?

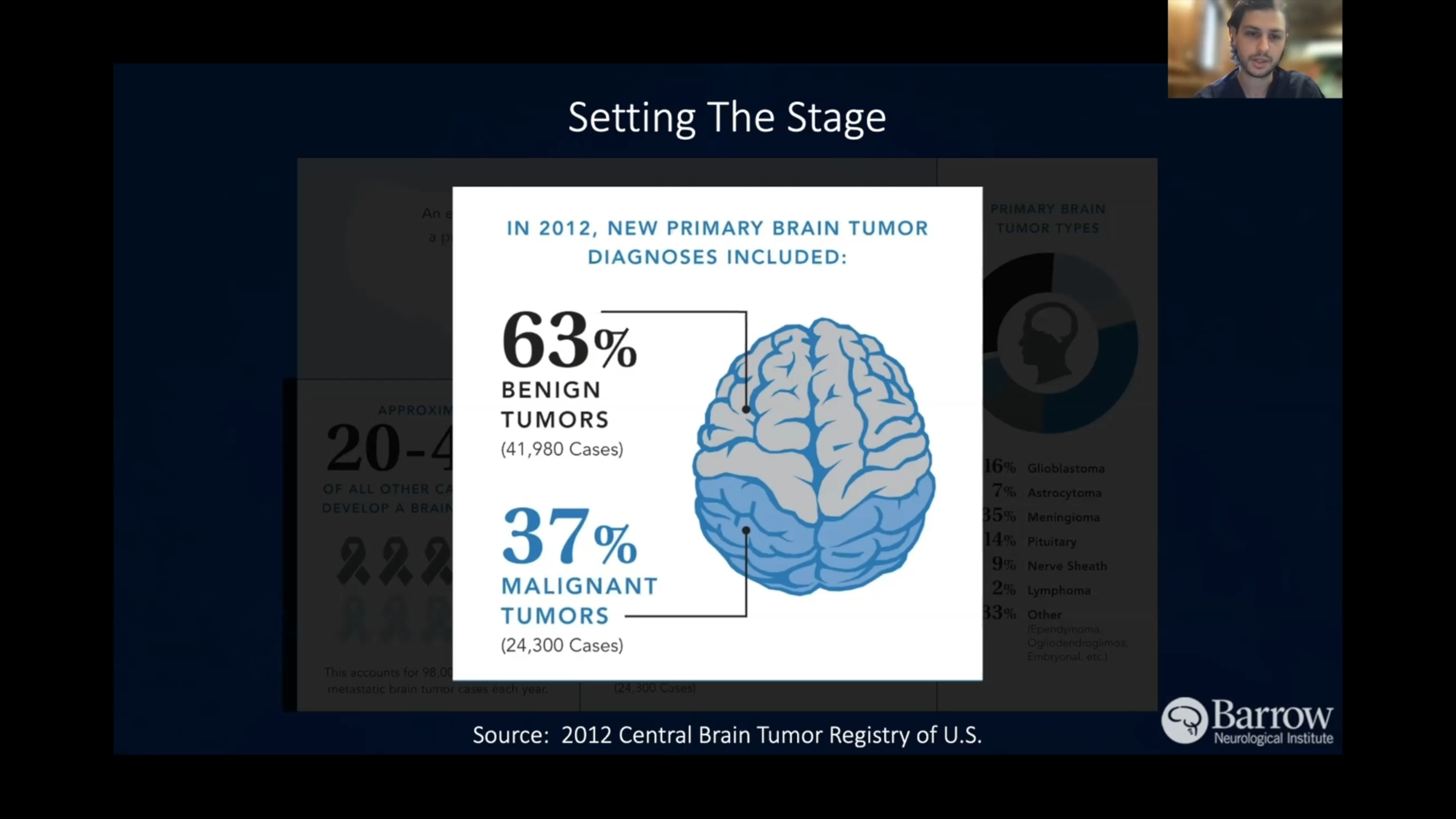

Oligodendrogliomas account for less than two percent of brain tumors in the U.S., with approximately 1,100 new diagnoses each year. These tumors are much less common than other gliomas, such as glioblastomas or astrocytomas.

As of 2023, an estimated 15,000 people live with an oligodendroglioma in the U.S.

Who gets oligodendrogliomas?

While rare, oligodendrogliomas are more commonly diagnosed in adults and occur slightly more often in men than in women. While they can also occur in children, this is far less common. In fact, for teens between the ages of 15 and 19, these tumors make up only 1.5 percent of primary brain tumors—and that number is even less for children younger than 15 years old.

Doctors diagnose most oligodendrogliomas in adults between 30 and 50. The average age at diagnosis for Grade 2 oligodendrogliomas is 43, and for Grade 3 oligodendrogliomas, it is 50.

Most oligodendrogliomas are not inherited, but a family history of brain tumors or gliomas can slightly increase the overall risk. The risk is still low, as oligodendrogliomas usually occur sporadically without a strong familial link.

What is the prognosis for those with oligodendrogliomas?

With regular treatment and monitoring, many people with oligodendrogliomas can live for years or even decades, especially those with low-grade tumors or favorable genetic markers.

As a whole, the five-year survival rate for oligodendrogliomas is 79.5 percent.

For Grade 2 oligodendrogliomas, the five- to 10-year survival rate can be as high as 90 percent with optimal treatment and ideal genetic factors.

The prognosis for Grade 3 oligodendrogliomas varies more, with five-year survival rates between 30 and 50 percent, depending on the response to treatment and genetic factors.

Ultimately, many factors can affect prognosis, including tumor grade and molecular type. Younger patients and those in good general health tend to have a better prognosis because they often tolerate surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation better.

Moreover, advances in treatments and targeted therapies continue to improve survival rates and quality of life for those diagnosed with oligodendrogliomas.

Can oligodendrogliomas be prevented?

Currently, there is no known way to prevent oligodendrogliomas from developing. They are sporadic tumors, meaning they tend to occur without clear, preventable risk factors.

Some cases are linked to rare genetic conditions, like neurofibromatosis type I (NF1) and Li-Fraumeni Syndrome, which increases the risk of some brain tumors, including oligodendrogliomas. However, these genetic syndromes are inherited, so the focus is on regular monitoring and early detection rather than prevention.

Additionally, no established environmental or lifestyle factors—like diet, exercise, or chemical exposure—have been shown to prevent oligodendrogliomas. High-dose ionizing radiation, often used in cancer treatment, can increase the overall risk of brain tumors. Still, such exposure is rare and usually unavoidable.

Advances in genetic research may one day help identify additional oligodendroglioma risk factors. The best approach remains to focus on early diagnosis and prompt treatment. For those with a family history or genetic predisposition, regular MRI screenings can help with early detection.