Dementias: Etiologies and Differential Diagnoses

Patricio F. Reyes, MD

Jiong Shi, MD, PhD

Division of Neurology, Barrow Neurological Institute, St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center, Phoenix, Arizona

Abstract

Early and accurate diagnosis is the major objective in dementia evaluation. To achieve this goal, a comprehensive examination must include a thorough medical history; careful medical and neurologic examinations; assessment of cognitive, behavioral, and activities of daily living; laboratory tests; and neuroimaging studies.

Key Words: activities of daily living, Alzheimer’s disease, behavior, cognition, dementia, Lewy body, neurodegeneration, neurofibrillary tangles, neuritic plaques, Parkinson’s disease

Abbreviations used: AD, Alzheimer’s disease; ApoE, apolipoprotein-E; CNS, central nervous system; CT, computed tomography; MR, magnetic resonance; NPH, normal pressure hydrocephalus; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; PD, Parkinson’s disease; PET, positron emission tomography; TBI, traumatic brain injury

The graying of the world has heightened interest in normal aging and dementia. This trend largely reflects that the elderly is the fastest growing segment of the population. Therefore, dementias, which usually affect the late middle-aged and elderly, have become a major health care problem.[1] Typically, patients with dementia exhibit gradual yet progressive decline in cognitive functions, changes in personality and behavior, and deterioration in their activities of daily living.[2]

Frequently, onset of symptoms is difficult to ascertain because normal older individuals may show similar manifestations. The symptom complex of dementia evolves over several months to years. Therefore, early recognition is crucial to offer comprehensive therapy that includes pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic strategies, psychosocial intervention, and advice for timely legal and financial planning. A major hurdle that needs to be overcome is the misperception by certain ethnic groups that dementia is a natural consequence of aging; hence, it requires no diagnostic or therapeutic intervention. It is imperative that educational programs designed to eradicate such a false notion incorporate culturally based and sensitive strategies.

Diagnosing and treating dementias have placed considerable financial strain on our healthcare system and individual families. Affected patients are forced to quit their jobs or to seek early retirement whereas spouses and other family caregivers may have to reduce their working hours to care for their loved ones. The same caregivers have to endure increased emotional and physical stress due to the protracted clinical course of many dementias. Furthermore, healthcare costs have been estimated to rise steeply when medical conditions are complicated by cognitive decline and behavioral symptoms. Management of these symptoms often requires sophisticated tests, special referrals, and expensive prescription drugs.[3]

Etiology and Differential Diagnosis

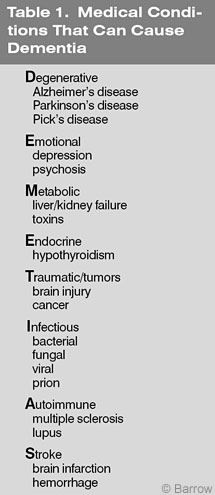

A wide spectrum of systemic and neurological disorders can give rise to signs and symptoms of dementia (Table 1). The differential diagnosis includes degenerative (Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, or Pick’s disease), emotional (depression), metabolic (organ failure), neoplastic (carcinomatous meningitis), traumatic (TBI), immunologic (multiple sclerosis), infectious (Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease), endocrine (hypothyroidism), nutritional (vitamin B12 deficiency), and cerebrovascular diseases.

Diagnosis can be challenging since most cases of dementia are in middle-aged and older individuals who are vulnerable to both systemic and neurologic diseases. Consequently, many are prescribed multiple medications that can produce or exacerbate neuropsychiatric symptoms or that cause drug interactions. Drug-related adverse events such as extrapyramidal symptoms associated with chronic neuroleptic exposure could easily be mistaken as evidence of Parkinson’s disease with dementia or as AD with Lewy bodies.

Among the several etiologic entities, degenerative CNS disorders compose the overwhelming majority.[4] When dealing with such diseases, there are fundamental tenets that should be noted. First, neurodegeneration takes several months or years to manifest clinically. Therefore, even when early signs and symptoms are confirmed by sensitive clinical measures, it must be assumed that the pathologic process began many months or years earlier. Its onset may be insidious yet its course is progressive. Neurodegeneration usually denotes bilateral brain involvement although neurologic signs may be asymmetrical. As the disease progresses, the process may become diffuse or multifocal caused by transsynaptic degeneration of afferent and efferent systems. Risk factors may be known but many entities are idiopathic.

Presenting symptoms may occur after certain emotional or physical trauma or exposure to certain medications, in particular those with strong anticholinergic properties, possibly exacerbating the cholinergic deficiency in AD.[5] Several years ago we reported patients who developed progressive dementia after receiving eye drops.[6] Death of a loved one may trigger depression, memory loss, and language difficulty whereas surgery and general anesthesia may herald persistent agitation, confusion, hallucinations, and memory difficulty. It would be prudent to perform neurobehavioral testing before surgery in vulnerable patients who need general anesthesia.

Among the neurodegenerative disorders, AD accounts for at least 65%, making it the most common cause of dementia among the middle-aged and older.[4] Ten to 15% have vascular dementia secondary to various forms of cerebrovascular disease. Nevertheless, recent neuropathologic studies have indicated that in 30 to 35% of cases, lesions associated with AD and vascular dementia coexist. PD, the third leading cause of dementia and considered for several decades as a primary extrapyramidal disorder, may be accompanied by dementia in at least 30% of cases.

Different etiologic factors may contribute to the development of dementia in PD. Clinically, classic PD with dementia is characterized by prominent deficits in executive function, presumably related to degeneration of connectivity between the prefrontal cortex and basal ganglia.[7] Basal ganglia strokes, concomitant AD, and Lewy body dementia also may lead to cognitive decline in PD and Parkinsonian cases associated with cognitive deficits. Less common etiologies include frontotemporal dementias as exemplified by Pick’s disease, Lewy body dementia, Parkinsonian syndromes such as progressive supranuclear palsy, prion disease, infections, neurotoxins, neoplasms, paraneoplastic syndromes, TBI, and metabolic, immunologic, nutritional, and endocrine disorders. A common laboratory finding observed in cognitively impaired patients is a low level of vitamin B12, most probably caused by changes in eating habits rather than by pernicious anemia. Intramuscular administration of vitamin B12 is indicated to correct the deficiency and to insure sufficient levels and body reserve.

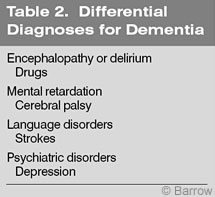

Other medical conditions that must be distinguished from dementia are delirium or encephalopathy, mental retardation, language disorders, and pseudodementia (Table 2).

Delirium, in general, is an acute process usually caused by toxic-metabolic conditions accompanied by fluctuating levels of consciousness and mental status. If the offending agent is promptly identified and specific treatment is delivered, neuropsychiatric manifestations could be reversed. Significant delay in management could result in persistent or progressive brain damage. In some instances, individuals with mental retardation may be erroneously labeled as demented due to their inherent cognitive and behavioral deficits and their lack of ability to perform normal activities of daily living. In many cases their neurobehavioral abnormalities are related to intrauterine and perinatal insults to the CNS from genetic or acquired anomalies.

Formal neuropsychological testing is an important tool to document various aspects and degrees of higher cortical dysfunction that could be used as the basis for recommending suitable special educational programs. Aphasias and language disorders can be difficult to distinguish from dementia if they are not attended by clear lateralizing neurologic signs. However, most cases are associated with focal or multifocal intracranial lesions that can affect memory, executive function, comprehension, verbal output, reading, writing, and the ability to follow commands. Patients also may have focal signs, and CT and MR imaging are helpful in verifying the type and distribution of lesions.

Pseudodementia generally refers to patients with depression, psychosis, and a history of drug abuse. Such cases can be difficult to diagnose because dementia can manifest with personality and behavioral alterations that can precede cognitive symptoms. They can mimic many of the signs and symptoms of dementia. Focal neurologic abnormalities are absent and a thorough neuropsychiatric history and assessment, including a formal neuropsychological and psychiatric evaluation, are essential in establishing the diagnosis.

Diagnosis

The diagnostic approach to dementia requires (1) a comprehensive history; (2) a complete physical and neurologic examination that should incorporate cognitive, behavioral, and activities of daily living assessment; and (3) laboratory and neuroimaging studies to rule in or out various systemic and neurologic conditions as well as to demonstrate the nature and anatomic distribution of intracranial structures.

Medical History

Many patients are unable to provide a reliable medical history; hence, caregivers become the source and must be encouraged to provide detailed, pertinent, and confirmatory information during initial and follow-up visits. Patients and caregivers, including spouses, may deny the presence or underestimate the severity of symptoms. It is crucial to seek reliable informants who are also willing to work with health care professionals.

In dementias, a comprehensive history should consist of careful documentation of the onset, evolution, and duration of symptoms; precipitating, exacerbating, and relieving factors; comorbid medical conditions; medication intake; foreign and domestic travel and associated signs and symptoms; occupation; exposure to neurotoxins and recreational drugs; family history; and previous treatment for sexually transmitted disorders. Symptoms may become evident to family members and friends after loss of a loved one, surgery, minor head trauma, or a urinary tract infection. Unexplained poor performance at work, motor vehicular accidents, unpaid bills, lack of interest in hobbies, asking the same questions, and other changes in personality and behavior may signify an evolving dementing process. Word-finding difficulties and progressive aphasia are commonly attributed to strokes and should be evaluated carefully because they could be early symptoms of AD or primary progressive aphasia.

A strong family history of early onset (before 60 years) dementia may indicate familial types of AD related to mutations of chromosomes 1, 14, or 21, whereas a similar history with late onset (after 65 years) might implicate an Apo-E 4 genotype, a risk factor gene that merely increases the chance of developing AD.[4,8]

Prominent psychiatric symptoms early in the clinical course may suggest frontotemporal dementia exemplified by Pick’s disease. Several years ago we reported the presence of Parkinsonian symptoms and visual hallucinations at autopsy in demented patients who turned out to have large numbers of senile plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, and Lewy bodies in the substantia nigra and cerebral cortex. We labeled them as AD with Lewy bodies.[9] Subsequent investigators assigned the term Lewy-body dementia, although we still believe that many such cases satisfy the clinical and neuropathological criteria for AD. In this patient group, antipsychotic agents and levodopa should be used with caution since both could lead to serious adverse reactions. Similar symptomatology may be seen in PD with dementia. PD with dementia usually manifests first with the typical symptoms of PD followed by dementia.

A relentlessly rapid form of dementia evolving within weeks or months is observed in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, a prion disease and the human counterpart of mad cow disease, which in rare cases can be genetically linked.[3,10] Other rare causes are neurotoxins, subacute metabolic conditions, organ failure, infections, and carcinomatous meningitis. Most recently, we had the opportunity to care for a late middle-aged man with rapidly progressive dementia who was found to have multiple dural fistulas. He recovered after endovascular surgery with minimal neurologic residua (see Multiple Dural Arteriovenous Fistulas Presenting with Rapidly Progressive Dementia: Case Report and Review of the Literature in this issue).

A more common treatable form of dementia is NPH, a syndrome characterized by gait difficulty, urinary incontinence, cognitive decline, and enlarged ventricles. Gait disturbance is frequently the most prominent sign whereas higher cortical deficits are relatively mild. Favorable as well as dramatic response may be seen after ventricular shunting if symptoms are recognized early and preceded by subarachnoid hemorrhage, meningitis, encephalitis, or head trauma. This group is referred to as secondary NPH. There is controversy as to how to manage idiopathic NPH, which includes patients with progressive dementia, many of whom may have AD, who develop gait abnormality and urinary incontinence without a history of intracranial events. In collaboration with our neurosurgical colleagues at our institution, we are prospectively evaluating and treating both patient populations. Those who satisfy our NPH criteria may undergo ventricular shunting with a programmable valve.

Physical and Neurological Examinations

It is essential that every patient with dementia undergo a thorough physical and neurological evaluation to search for signs of systemic diseases and for focal and/or multifocal neurologic deficits. Uncontrolled hypertension, cardiac rhythm irregularity, valvular heart disease, carotid bruit, and peripheral arterial disease accompanied by stepwise progression of dementia and focal signs are suggestive of vascular dementia. Ischemic and hemorrhagic lesions in the thalamus, prefrontal region, medial temporal lobe, and associated areas involving small, medium, and large caliber arteries are well-known correlates of vascular dementia. Temporal tenderness, muscle aches, joint pains, and abnormal pulses in patients with unexplained headaches and blurred vision may indicate vasculitis or vasculopathy. Cranial bruising and ecchymoses may indicate TBI that can lead to contusion, subdural hematoma, and parenchymal hemorrhage.

A thorough neurologic examination is equally crucial in every dementia evaluation. It must incorporate test measures to evaluate activities of daily living, cognition, and behavior.

Dementia followed by Parkinsonian signs such as tremor, masked facies, facial seborrhea, bradykinesia, rigidity, and gait abnormality plus a history of visual hallucination and mood fluctuation are important features of AD with Lewy bodies or Lewy body dementia. In contrast, known PD patients who develop cognitive impairment could have PD dementia, PD and AD, or PD associated with strokes.[7,9] Parkinsonism accompanied by a history of falls with or without fractures, abnormal vertical eye movements, marked rigidity, extensor plantar responses, and impaired cognition are suggestive of progressive supranuclear palsy. Increased reflexes, extensor plantar responses, and sensory deficits referable to posterior column damage are commonly associated with a vitamin B12 deficiency. This condition can either cause dementia or complicate a dementing process since affected patients may be deprived of appropriate nutrition. In either case, parenteral administration of vitamin B12 to patients when their serum level of vitamin B12 is below 400 pg/ml may improve some of the symptoms. In our experience pernicious anemia is exceedingly rare, and the overwhelming majority of demented patients with a low level of vitamin B12 suffer from poor nutrition.[10]

Myoclonic jerks may take the form of sudden twitching of fingers, a limb, or half of or the entire body without a concomitant change in mental status. They may be stimulated by noise or touch, and ataxia may be prominent in some cases. These signs must be carefully noted because they are common in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, which is transmissible by tissue-to-tissue contact, and is usually followed by death within weeks or months. Asymmetrical distribution of muscle weakness, pathologic reflexes, and sensory changes indicate structural pathologic processes such as neoplasms, strokes, hematomas, and brain abscesses. Frontal lobe release signs such as glabellar, snout, and grasp reflexes are normally associated with neurodegenerative disorders such as AD and PD.

Cognitive and behavioral testing is essential to determine the nature and severity of impairments of cognition, behavior, and activities of daily living.[2] These impairments usually affect the late middle-aged and elderly, and the degree of their deficits affects their social and/or professional functioning. Some of the validated test measures we employ in clinical practice are the Mini-Mental State Examination, Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale, Dementia Rating Scale, Geriatric Depression Scale, Neuropsychiatric Inventory, and Progressive Deterioration Scale. Data from these tests are then utilized to establish the type and degree of abnormalities, disease stage, and rationale for management. A formal neuropsychological assessment may be used to better define various aspects of cognition, behavior, personality, language, and motoric function. In early and atypical cases, sequential neuropsychological testing can be extremely helpful in demonstrating subtle or progressive signs and symptoms.

Laboratory and Neuroimaging Studies

Appropriate diagnostic tests are necessary to insure prompt identification of offending agent(s) and timely delivery of treatment. It also allows clinicians to exclude potentially treatable and reversible conditions. Complete blood count, sedimentation rate, complete metabolic profile, thyroid function studies, venereal disease research laboratory test, serum B12, folic acid and homocystine levels, urinalysis, and brain CT or MR imaging without contrast are evaluated routinely.

If intracranial mass lesions are suspected, CT or MR imaging with and without contrast is indicated. MR imaging, a noninvasive procedure, can be used to exclude extra- or intracranial occlusive disease. PET, a diagnostic tool that uses radiolabeled compounds to verify metabolic brain changes, may differentiate atypical cases of AD from frontotemporal dementia. EEG is helpful in patients with possible epilepsy, Herpes simplex encephalitis, and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease.

In most instances relevant CSF studies are needed to diagnose CNS infections, including prion disease. In particular, elevated CSF levels of the 14-3-3 protein, a cell membrane protein, is useful in supporting the antemortem diagnosis of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. PCR, smears, and cultures that detect viral and bacterial antigen and antibody levels in serum and/or CSF are indicated for CNS infections. Twenty-four hour urine levels of heavy metals such as arsenic, mercury, manganese, and lead can be obtained in patients with exposure to neurotoxins. In the appropriate clinical setting, human immunodeficiency virus and related tests are appropriate to exclude sexually transmitted disorders.

Societal Issues in Dementias

Early and accurate diagnosis of dementia requires comprehensive and expensive medical and neurologic assessment. The cost of caring for demented patients will continue to rise as we develop more sophisticated diagnostic tools as well as new therapeutic modalities. Once the diagnosis is achieved, an affected patient may be deprived of his or her life-long career and financial reward; the rights to vote, to enter into a contract, or to make personal decisions; and opportunities to assume key positions in social organizations, politics, religion, business, military units, and institutions of higher learning.

Conclusion

Dementia is a symptom complex that requires comprehensive medical and neurobehavioral assessment. Establishing its diagnosis and identifying its etiology as early and accurately as possible are essential to offer affected individuals the most appropriate therapy.

References

- Fuchs GA, Gemende I, Herting B, et al: Dementia in idiopathic Parkinson’s syndrome. J Neurol 251 Suppl 6:VI/28-VI/32, 2004

- Helpern JA, Jensen J, Lee SP, et al: Quantitative MRI assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. J Mol Neurosci 24:45-48, 2004

- Johnson RT: Prion diseases. Lancet Neurol 4:635-642, 2005

- Mendez HA: Comment on The APOE-epsilon4 allele and Alzheimer disease among African Americans, whites, and Hispanics by Tang MX, Stern Y, Marder K et al. JAMA 279(10):751-755, 1998. JAMA 280:1663, 1998

- Pokorski RJ: Differentiating age-related memory loss from early dementia. J Insur Med 34:100-113, 2002

- Reyes PF, Dwyer BA, Schwartzman RJ, et al: Mental status changes induced by eye drops in dementia of the Alzheimer type. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 50:113-115, 1987

- Roman GC, Royall DR: A diagnostic dilemma: Is “Alzheimer’s dementia” Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, or both? Lancet Neurol 3:141, 2004

- Silverberg GD, Mayo M, Saul T, et al: Alzheimer’s disease, normal-pressure hydrocephalus, and senescent changes in CSF circulatory physiology: A hypothesis. Lancet Neurol 2:506-511, 2003

- Swartz RH, Black SE, Sela G, et al: Cognitive impairment in dementia: Correlations with atrophy and cerebrovascular disease quantified by magnetic resonance imaging. Brain Cogn 49:228-232, 2002

- Wolters M, Strohle A, Hahn A: Cobalamin: A critical vitamin in the elderly. Prev Med 39:1256-1266, 2004