Acquired Hindbrain Herniation and Intracranial Hypotension After Intracranial Cysto-Atrial Shunt Placement: Case Report

Wouter I. Schievink, MD*

Archana C. Lucchesi, MD†

Nicholas Theodore, MD

Robert F. Spetzler, MD

Division of Neurological Surgery, and †Neuroradiology Barrow Neurological Institute, St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center, Phoenix, Arizona

Current Address: *Cedars-Sinai Neurosurgical Institute, Los Angeles, CA, †East Valley Diagnostic Imaging, Mesa, AZ

Abstract

Acquired hindbrain herniation associated with intracranial hypotension is common in patients with spontaneous spinal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leaks or after a lumboperitoneal shunt is placed. We report a 51-year-old woman who underwent a craniotomy for marsupialization of an arachnoid cyst of the cerebellopontine angle followed by placement of a cystoperitoneal shunt. At age 52, she underwent placement of a valveless cysto-atrial shunt. Seven years later she underwent a suboccipital craniectomy for decompression of an acquired hindbrain herniation that was associated with diffuse meningeal enhancement, but her symptoms recurred and progressed due to intracranial hypotension. A medium-pressure valve was placed in the cysto-atrial shunt system. Her symptoms greatly improved, the meningeal enhancement resolved, and the “brain sagging” improved. Her case demonstrates that symptomatic acquired hindbrain herniation in the setting of intracranial hypotension can be caused by an overdraining CSF shunt from the intracranial compartment.

Key Words: cerebrospinal fluid shunt, Chiari malformation, headache, intracranial hypotension, intracranial pressure

Intracranial hypotension is an important cause of postural headaches (i.e., headaches exacerbated by an upright position and relieved by recumbency). The most common causes of intracranial hypotension in neurosurgical practice are lumbar puncture, overdraining cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) shunts, and craniospinal trauma. A spontaneous form of intracranial hypotension has been recognized for more than 60 years,13 but only recently has it been diagnosed on a regular basis.1,4,7,9,11,15,16 The most common causes of spontaneous intracranial hypotension are spinal CSF leaks from dural rents or meningeal diverticula.15,16

Characteristic findings of intracranial hypotension on magnetic resonance (MR) imaging include pachymeningeal enhancement, subdural fluid collections, and “brain sagging.”1,4,6,7,9,11,12,15,16 When the intracranial hypotension is caused by an overdraining lumboperitoneal shunt or spinal CSF leak, brain sagging often appears as caudal displacement of the cerebellar tonsils that resembles a Chiari type I malformation.4,6,7,9,10,15-18 We report a patient with chronic symptomatic intracranial hypotension who developed cerebellar tonsillar herniation. The herniation resembled a Chiari type I malformation and was caused by an overdraining shunt from an intracranial arachnoid cyst to the atrium.

Case Report

A 51-year-old woman presented with a 2-year history of progressive headaches, nonvertiginous dizziness, nausea, and gait difficulties. Examination showed gait ataxia. Computerized tomography (CT) showed a large arachnoid cyst in the right cerebellopontine angle causing mass effect. A craniotomy was performed, the arachnoid cyst was marsupialized, and a ventricular catheter was placed into the cyst cavity and attached to a Rickham reservoir. After surgery, her symptoms improved and CT showed satisfactory decompression of the arachnoid cyst.

Six months later, her headache and dizziness recurred. CT showed that the arachnoid cyst had reaccumulated. The cystic fluid was aspirated and her symptoms improved. There was no evidence of tonsillar herniation. She underwent placement of a cystoperitoneal shunt, but her symptoms improved only marginally.

Three months later a distal shunt obstruction was diagnosed, and the cystoperitoneal shunt was converted to a cysto-atrial shunt. The intracranial catheter and Rickham reservoir were left in situ and connected to a valveless Pudenz cardiac catheter, which was placed percutaneously into the right atrium. Distal slits on the Pudenz catheter prevent reflux of blood into the system. After surgery, the patient’s headaches and dizziness again improved. CT confirmed that the size of the arachnoid cyst had decreased. Several months later, however, she developed true vertigo and multiple syncopal episodes. Extensive cardiac evaluations of the syncope failed to reveal a cause.

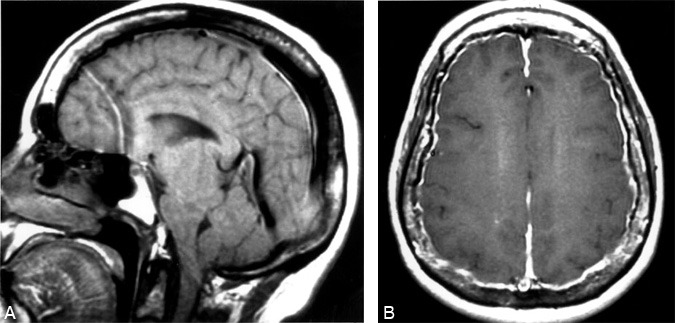

Three years after the cysto-atrial shunt was placed (at age 55), the patient presented to the Emergency Department with new right face and hemicorporal numbness, persistent vertigo, syncopal spells, and occipital headaches that were exacerbated by the upright position. Her neurological examination was normal. MR imaging showed diffuse thin pachymeningeal enhancement and brain sagging, including cerebellar tonsillar herniation (Fig. 1). At that time, these changes were not recognized as typical of intracranial hypotension. Lumbar puncture showed an opening pressure of 5 cm H2O, and her CSF examination was normal.

Her symptoms persisted for 4 years at which time another MR imaging study was obtained. This study showed progression of the cerebellar tonsillar herniation and meningeal thickening (no gadolinium was given). She underwent a suboccipital craniotomy and C1 laminectomy, and the posterior fossa was decompressed. Her symptoms improved for several months but then recurred.

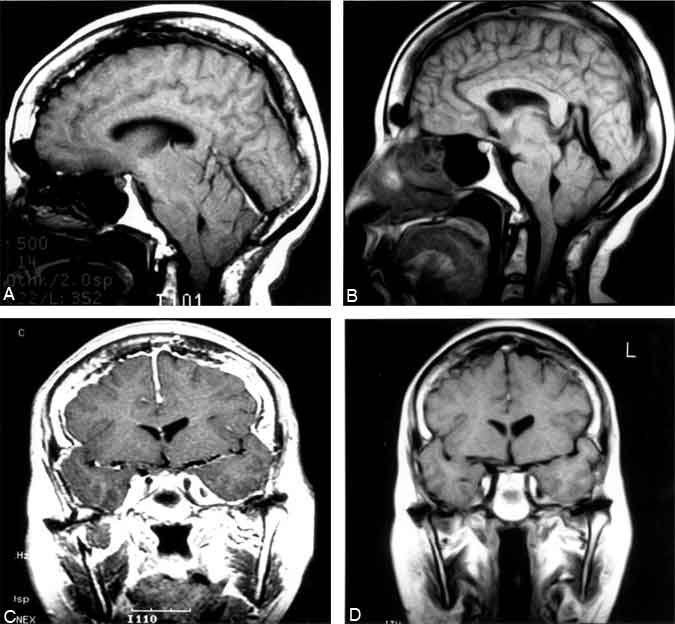

Nine years after the cysto-atrial shunt was placed and 2 years after the posterior fossa decompression (at age 61), the patient returned with worsening headaches, vertigo, and syncope. The headaches were now chronic and no longer positional. Again, her neurological examination was normal. MR imaging showed florid diffuse pachymeningeal enhancement and brain sagging with persistent hindbrain herniation (Fig. 2). Intracranial hypotension was diagnosed.

CT myelography was successfully performed at the L2-L3 level, but the opening pressure was 0 cm H2O and no CSF could be obtained. This study showed that the CSF shunt and the cavity of the arachnoid cyst at the cerebellopontine angle communicated with the spinal subarachnoid space. There was no evidence of a spinal CSF leak. Delayed imaging showed a small cervical syrinx.

The patient was taken to the operating room, and a medium-pressure valve was placed between the Rickham reservoir and the cardiac catheter. She recovered well from the surgery. MR imaging obtained a week later showed that the meningeal enhancement had resolved and the brain sagging had improved (Fig. 2). Six weeks after surgery, the patient reported that her headaches and vertigo had improved “90%” and that she had experienced no syncopal events.

Discussion

Cerebellar tonsillar herniation resembling a Chiari type I malformation in the setting of intracranial hypotension is a well-recognized manifestation of spontaneous spinal CSF leaks 4,6,7,9,11,15 or lumboperitoneal shunt placement.2,10,17,18 Although overdraining ventriculoperitoneal shunts can also be associated with intracranial hypotension and meningeal enhancement on MR imaging or CT, cerebellar tonsillar herniation is rare under those circumstances.7 In fact, ventriculoperitoneal shunting often is the initial treatment for acquired cerebellar tonsillar herniation after lumboperitoneal shunt placement or for Chiari type I malformations when any degree of hydrocephalus is demonstrated.2,10,17,18

In our patient, the intracranial hypotension and cerebellar tonsillar herniation were caused by an overdraining, valveless CSF shunt from the intracranial arachnoid cyst to the atrium. Because of the cerebellar tonsillar herniation, a CT myelogram was obtained to rule out a spinal source of CSF leakage. Although this study showed no spinal CSF leak, it clearly demonstrated that the CSF shunt and the arachnoid cyst in the cerebellopontine angle communicated with the spinal subarachnoid space. Hassounah and Rahm5 reported a patient with an asymptomatic cerebellar tonsillar herniation who had undergone shunting for a prepontine arachnoid cyst. They suggested that communication between the intracranial arachnoid cyst and the spinal subarachnoid space was necessary to produce a pressure differential between the cranial and spinal compartments.

A syrinx is frequently associated with acquired cerebellar tonsillar herniation after a lumboperitoneal shunt has been placed.2,3,10,17,18 Syringomyelia, however, has not been associated with spontaneous intracranial hypotension, with the possible exception of a patient reported by Morioka and colleagues.8,14 The reason for this discrepancy is unclear. Possibly, an extended duration of intracranial hypotension or high CSF flow in patients with lumboperitoneal shunts compared to those with spontaneous spinal CSF leaks could play a role. In our patient MR imaging did not show a syrinx, but a delayed CT myelogram demonstrated a small cervical syrinx.

Surgical decompression of acquired cerebellar tonsillar herniation has been reported in several patients with lumboperitoneal shunts 2,10,18 and in one patient with a spontaneous spinal CSF leak.15 Like most of those patients, our patient also experienced only temporary and partial resolution of symptoms after decompression. Her symptoms recurred and progressed after some time because of untreated intracranial hypotension. Because sudden interruption of a chronic CSF leak can cause symptomatic “”rebound”” intracranial hypertension,15 we elected to place a medium-pressure valve instead of a high-pressure valve in our patient who had had an overdraining CSF shunt for a long time.

In conclusion, acquired symptomatic cerebellar tonsillar herniation in the setting of intracranial hypotension may be caused by an overdraining shunt from the intracranial compartment.

References

- Blank SC, Shakir RA, Bindoff LA, et al: Spontaneous intracranial hypotension: Clinical and magnetic resonance imaging characteristics. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 99:199-204, 1997

- Chumas PD, Armstrong DC, Drake JM, et al: Tonsillar herniation: The rule rather than the exception after lumboperitoneal shunting in the pediatric population. J Neurosurg 78:568-573, 1993

- Fischer EG, Welch K, Shillito J, Jr: Syringomyelia following lumboureteral shunting for communicating hydrocephalus. Report of three cases. J Neurosurg 47:96-100, 1977

- Fishman RA, Dillon WP: Dural enhancement and cerebral displacement secondary to intracranial hypotension. Neurology 43:609-611, 1993

- Hassounah MI, Rahm BE: Hindbrain herniation: An unusual occurrence after shunting an intracranial arachnoid cyst. Case report. J Neurosurg 81:126-129, 1994

- Kasner SE, Rosenfeld J, Farber RE: Spontaneous intracranial hypotension: Headache with a reversible Arnold-Chiari malformation. Headache 35:557-559, 1995

- Mokri B, Piepgras DG, Miller GM: Syndrome of orthostatic headaches and diffuse pachymeningeal gadolinium enhancement. Mayo Clin Proc 72:400-413, 1997

- Morioka T, Shono T, Nishio S, et al: Acquired Chiari I malformation and syringomyelia associated with bilateral chronic subdural hematoma. Case report. J Neurosurg 83:556-558, 1995

- Pannullo SC, Reich JB, Krol G, et al: MRI changes in intracranial hypotension. Neurology 43:919-926, 1993

- Payner TD, Prenger E, Berger TS, et al: Acquired Chiari malformations: Incidence, diagnosis, and management. Neurosurgery 34:429-434, 1994

- Rando TA, Fishman RA: Spontaneous intracranial hypotension: Report of two cases and review of the literature. Neurology 42:481-487, 1992

- River Y, Schwartz A, Gomori JM, et al: Clinical significance of diffuse dural enhancement detected by magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurosurg 85:777-783, 1996

- Schaltenbrand G: Neuere Anschauungen zur Pathophysiologie der Liquorzirkulation. Zentralbl Neurochir 3:290-299, 1938

- Schievink WI, Atkinson JLD: Spontaneous intracranial hypotension [letter]. J Neurosurg 84:151-152, 1996

- Schievink WI, Meyer FB, Atkinson JLD, et al: Spontaneous spinal cerebrospinal fluid leaks and intracranial hypotension. J Neurosurg 84:598-605, 1996

- Schievink WI, Morreale VM, Atkinson JLD, et al: Surgical treatment of spontaneous spinal cerebrospinal fluid leaks. J Neurosurg 88:243-246, 1998

- Sullivan LP, Stears JC, Ringel SP: Resolution of syringomyelia and Chiari I malformation by ventriculoatrial shunting in a patient with pseudotumor cerebri and a lumboperitoneal shunt. Neurosurgery 22:744-747, 1988

- Welch K, Shillito J, Strand R, et al: Chiari I “”malformations”” –an acquired disorder? J Neurosurg 55:604-609, 1981