Construct Validity of the BNI Screen for Higher Cerebral Functions in School-Age Children

George P. Prigatano, PhD

Saurabh Gupta, MC

Vicky T. Lomay, PhD

Division of Neurology, Barrow Neurological Institute, St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center, Phoenix, Arizona

Abstract

The BNIS-C was designed to be sensitive to developmental changes in normal school-age children and to the effects of various forms of brain pathology. In a standardization study of 232 children, a multiple regression analysis revealed that the BNIS-C Total score could be predicted reliably as a function of the children’s grade, age, and scores on the Wechsler Vocabulary and Block Design Scales (R=+.785, R2=.616). In a study of TBI in school-age children, a similar finding was obtained when the admitting GCS score was added to the equation (R=+.776, R2=.603). These findings support the construct validity of the BNIS-C.

Key Words: Children, higher cerebral functioning, neuropsychological tests, traumatic brain injury, validity

Abbreviations used: BNIS-C, BNI Screen for Higher Cerebral Functions for School-Age Children; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; TBI, traumatic brain injury; WISC, Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children

The rationale and initial validation studies of the BNIS-C were recently reported.[3] A test-retest reliability study on the BNIS-C showed that the Total score between the two testing periods was within ± 2 points in 85% of the children tested. The test-retest correlation coefficient was +.812.6 This study suggested that the BNIS-C can be reliably administered to school-age children.

The BNIS-C was constructed to be sensitive to developmental changes and to the effects of brain injury.[3] Two recent investigations provide information relevant to the question of the construct validity of the BNIS-C. The first was the standardization study in which 232 children functioning normally within the public school system (Grades 1 through 8) were administered the BNIS-C along with other neuropsychological tests.[5] The second was a study on parental perspectives on recovery and social integration after TBI in school-age children.[2]

The current study was designed to test two hypotheses. The first hypothesis was that the Total score on the BNIS-C would significantly and positively correlate with age (6 through 14 years) and grade (1 through 8). The second was that the BNIS-C Total score would significantly correlate with the severity of TBI during childhood as measured by admitting GCS score.[8] Higher GSC scores mean less severe brain injury, and higher BNIS scores mean better performance. Thus, these two dimensions should correlate positively.

Multiple regression analyses were conducted to determine the strength of these relationships to predict level of performance. Premorbid cognitive abilities are known to influence cognitive performance after brain injury.[1] Consequently, children’s vocabulary and visuospatial problem-solving abilities, as measured by the WISC-III or IV,10 were also included in the data analyses.

Study 1. BNIS-C Total Score as a Function of Age, Grade, and Estimates of Intelligence

Details concerning the recruitment and selection of subjects and of the neuropsychological tests administered are presented in the test and administration manual for the BNIS-C.[5]

Description

Two-hundred and thirty-two children in Grades 1 through 8, primarily from the Creighton Public School District in Phoenix, Arizona, were tested. There were 139 girls (59.9%) and 93 boys (40.1%) Of the 232 children, 204 (87.9%) were right-handed.

All children were administered the BNIS-C and the WISC-III or WISCIV Vocabulary and Block Design scales in addition to other neuropsychological tests.[5] Time to complete the BNIS-C was recorded when the test was administered. There was no significant difference in the scale scores of children in different grades on the Vocabulary (F = 1.567, df =7,224, p=.146) or Block Design Scales (F =.547, df =7,224, p= .798). Their mean performances were within the average range. All children were judged to be performing normally in a classroom environment and received no form of special education services.

Results

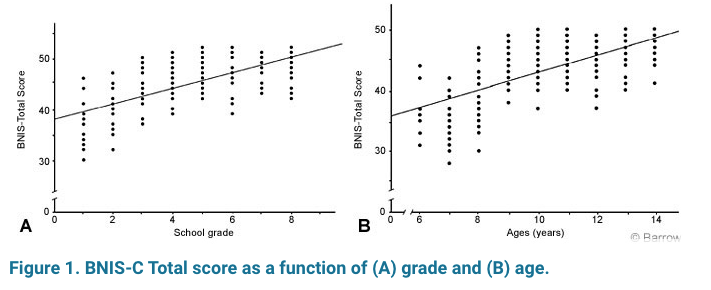

Children performing normally in the public school environment predictably showed a strong correlation between age and grade level (r=+.976, n=232, p=.000). The correlations between the BNIS-C Total score and grade level (r= +.712, n=232, p=.000) and between the BNIS-C Total score and age (r= +.671, n=232, p=.000) were strongly positive (Fig. 1).

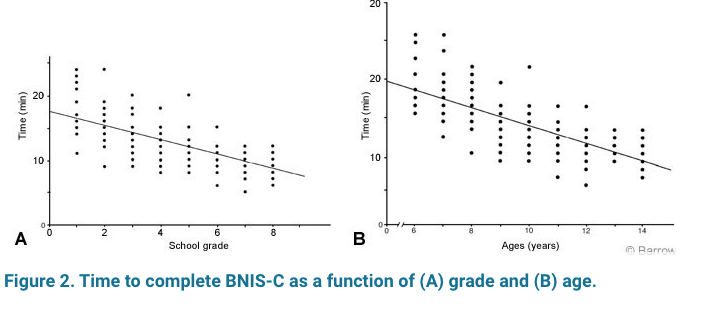

Younger children took longer to complete the task than older children (Fig. 2). The same was true for children at different grade levels. The strength of the correlation was identical for the two comparisons (r=–.725, n=229, p=.000). These findings support the first hypothesis that the BNIS-C Total and time scores are developmentally sensitive.

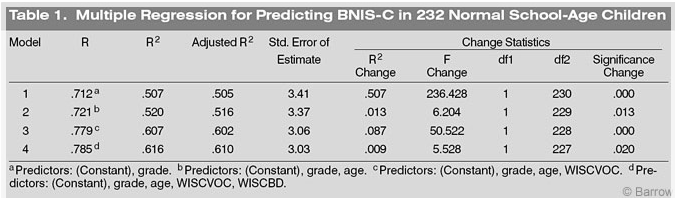

A multiple regression equation was calculated for the study sample to predict BNIS-C Total scores. The first predictor was grade level, and the second predictor was age. The third predictor was score on the WISC-III or IV Vocabulary Scale, and the fourth predictor was score on the Block Design Scale (Table 1). In these normal children, 50% of the variance was accounted for by grade (which strongly correlates with age). Level of intelligence (as estimated from the Vocabulary and Block Design Scale scores) contributed an additional 9% of the variance.

Study 2. BNIS-C Total Score and Severity of TBI in School-Age Children

Description

A brief description of a Maricopa County study on the care of TBI children, sponsored by the Arizona Department of Health Services, Office of Special Health Care Needs via grant support from the Legacy Foundation, can be found elsewhere.[2] That recently completed study included 81 children with a documented history of TBI and 19 trauma control subjects who had sustained a traumatic injury other than a TBI. Admitting GCS scores were available from 85 of these children, who were also in Grades 1 through 8. Of these 85 children, 51 were boys (62%) and 34 were girls. All children were in the postacute phase of their injuries. Mean chronicity (time since injury when tested) ranged from 1 to 3.62 years.

The 85 children were administered the BNIS-C and WISC-III Vocabulary and Block Design Scales along with additional neuropsychological tests.[2] Time to complete the BNIS-C was recorded when the test was administered.

Results

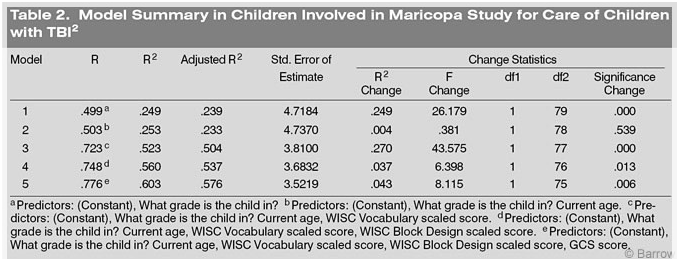

The correlation between the BNIS-C Total score and age was +.484 (n=97, p=.00). The correlation between grade level and the BNIS-C and Total score was similar (r=+.499, n=91, p=.000). As predicted, the BNIS-C Total score correlated significantly with admitting GCS score (r=+.333, n=83, p=.002).

A multiple regression analysis was performed on this sample of subjects to predict the BNIS-C Total score. The same variables were entered into the equation and in the same order as performed in Study 1. The GCS score was added last (Table 2). Grade level contributed an R2 value of .249, about half of that found in normally functioning children (Table 1). Vocabulary level, perhaps a partial measure of premorbid functioning in these children, contributed an additional 27% of the variance. Scores on the Block Design Scale contributed 3% of the variance. Admitting GCS score contributed an additional independent 4% of the variance. However, children with a severe TBI (GSC scores between 3 and 8) often have low scores on the Vocabulary and Block Design scales. Thus, these latter variables were also co-correlated.

Discussion

Most neuropsychological tests correlate with age and level of education.[7] The findings are most pronounced in normal individuals,[9] and the strength of these relationships typically decreases after an individual sustains a significant brain injury.[7]

In the standardization study of the BNIS for adults,4 age significantly (but negatively) correlated with the BNIS Total scores (r=-.55, n=197, p=.000). The correlation with level of education was less robust, but many of the elderly subjects in the study had fewer than 12 years of formal schooling (r =+.31, n= 197, p=.006).

In school-age children, age and education are highly correlated. However, the effects of education (grade level) relate to the level of performance on the BNISC. The magnitude of that relationship is reduced by a childhood brain injury. This study clearly documented the effect of premorbid intelligence on level of performance on the BNIS-C after a childhood brain injury. Collectively, these findings support the proposition that the BNIS-C is a clinically useful screening test of neuropsychological functioning in school-age children. Pre- and postmorbid characteristics of the child must be considered when interpreting performance on this screening test.

References

- Grafman J, Salazar A, Weingartner H, et al: The relationship of brain-tissue loss volume and lesion location to cognitive deficit. J Neurosci 6:301-307, 1986

- Prigatano GP: Community and school re-integration after childhood traumatic brain injury (abstract). Course Handouts, American Academy of Physical Medical Rehabilitation. AAPMR Org, Chicago, IL, 2004

- Prigatano GP: The BNI Screen for Children: Rationale and initial validation. Barrow Quarterly 20:27-32, 2004

- Prigatano GP, Amin K, Rosenstein LD: Administration and Scoring Manual for the BNI Screen for Higher Cerebral Functions. Phoenix: Barrow Neurological Institute, 1995

- Prigatano GP, Gagliardi CJ: BNI Screen for Higher Cerebral Functions in School-Age Children: A Manual for Administration and Scoring. Phoenix: Barrow Neurological Institute, 2005

- Prigatano GP, Gupta S, Lomay VT: Test-retest reliability of the BNI Screen for Higher Cerebral Functions for School-Age Children. Barrow Quarterly 21:22-24, 2005

- Prigatano GP, Parsons OA: Relationship of age and education to Halstead test performance in different patient populations. J Consult Clin Psychol 44:527-533, 1976

- Teasdale G, Jennett B: Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness. A practical scale. Lancet ii:81-84, 1974

- Vega A, Jr., Parsons OA: Cross-validation of the Halstead-Reitan tests for brain damage. J Consult Psychol 31:619-625, 1967

- Wechsler D: Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children. Administration and Scoring Manual. San Antonio, Texas: The Psychological Corporation, 2003