Barrow Reveals Findings From Latest Concussion Survey

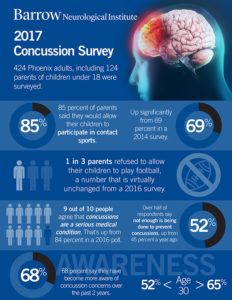

Despite increased emphasis on concussion education and player safety, one-third of Valley parents won’t allow their children to play football, according to a new survey by Phoenix’s Barrow Neurological Institute.

At the same time, 85 percent of parents say they will allow their children to play contact sports – a jump from 69 percent in a similar 2014 survey. The sentiment about football was consistent with a survey conducted last year.

The poll was conducted to determine public response to the increased visibility of concussions and brain injuries in sports.

“It is clear that parents continue to view football as more dangerous than other contact sports,” said Dr. Javier Cárdenas, director of the Barrow Concussion and Brain Injury Center at Barrow Neurological Institute, which is part of Dignity Health St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center. “As parents learn more about concussion treatment and diagnosis, they have become more willing to allow their children to play contact sports but make a notable exception for football.”

Dr. Cárdenas serves on the NFL’s Head, Neck and Spine Committee, working as an Unaffiliated Neurotrauma Consultant and sideline observer at Arizona Cardinals home games. He also serves as a sideline concussion observer at Arizona State University home football games.

In Arizona, the survey tracks with declining participation in 11-player high school football. In 2016-17, 17,858 boys and girls played 11-person high school football in Arizona, down from 20,929 the previous season, a drop of 15 percent, according to the National Federation of State High School Associations.

Football has by far the largest participation numbers and highest number of concussions among high school sports, but girls’ soccer has the highest percentage of players sustaining concussions. Nine out of 10 parents said they would allow their children to play soccer.

Concussion worries aren’t limited to football. Concussion accounts for 31 percent of all injuries sustained in cheerleading, according to a 2015 study published in the journal Pediatrics. But the study noted that cheerleading’s concussion rates are far lower than all other sports combined.

The survey revealed that 90 percent of respondents agree that concussions are a “serious medical condition” – a significantly higher percentage than in previous studies in 2014 (85 percent) and 2016 (84 percent). Dr. Cárdenas cited increased media coverage of concussions – especially in pro sports – as a factor in the wider public understanding of brain injuries.

Dr. Cárdenas said parents of patients in his clinic are showing increasing concern for the long-term effects of multiple concussions.

“I have seen parents withdraw their children from all sports that had any risk of concussion,” Dr. Cárdenas said. “More parents and families are assessing the risk of concussion based on an individual sport – and some are waiting to enroll their kids in sports that have a higher risk of concussion, fearing long-term exposure and higher risk at younger ages.”

Dr. Cárdenas said parents should be aware of a major gap in concussion protocols between high school and club sports. “At the high school level, concussion protocols are mandated by state federations,” he said. “Clubs generally do not have such governance, and it’s really the wild West in terms of concussion policies.”

The Barrow concussion awareness study was conducted in July 2017 with a sample of 424 Phoenix-area adults selected randomly. A similar series of questions was added to the January 2016 and February 2014 WestGroup Research surveys. The margin of error is plus or minus 5 percent at 95 percent confidence for the full sample (424) and plus or minus 8.8 percent among parents (124).